635938 Preisdatenbank Los(e) gefunden, die Ihrer Suche entsprechen

635938 Lose gefunden, die zu Ihrer Suche passen. Abonnieren Sie die Preisdatenbank, um sofortigen Zugriff auf alle Dienstleistungen der Preisdatenbank zu haben.

Preisdatenbank abonnieren- Liste

- Galerie

-

635938 Los(e)/Seite

A Lecoultre Art Deco desk clock, with simulated tortoiseshell stand. Height 6.5 cm. CONDITION REPORT: The movement does wind but is not currently ticking. The pointers will not adjust. The winding crown does pull out but is not operating the hands. The chrome surround to the dial is a little scratched in places but in generally good order. The painting to the numerals and pointers is a little faded. The face appears to be in generally good condition. The stand is in good order with no significant issues.

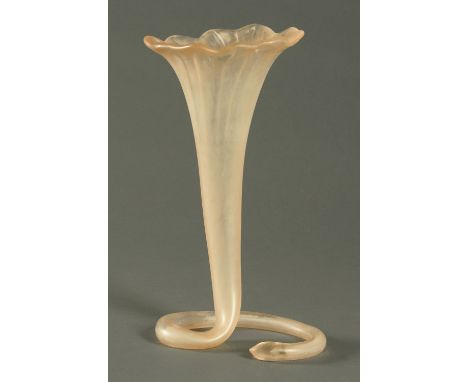

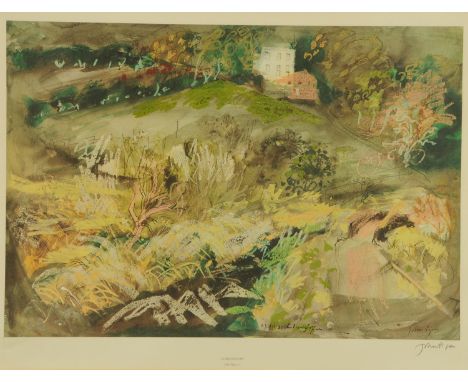

John Piper, screen print, "Clamecy". 77.5 cm x 58.5 cm, Limited Edition 85/100, signed, with copy invoice from Christie's Contemporary Art dated 1986 for £250 (see illustration). ARR CONDITION REPORT: The print itself is in very good condition with no issues. The white card mount has some water staining to the bottom edge. The mount is browned in places. The picture needs remounting.

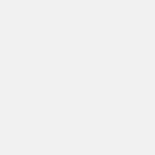

A pair of French gilt bronze Art Nouveau candlesticks, circa 1880, converted to electricity. CONDITION REPORT: These are both currently plugged in and lit. The bases are in generally good condition with no visible damage. They are both a little dirty. They have both been drilled in one place to allow the flex through the base. The flex passes through a natural gap between the leaves at the top.

An Art Deco Carltonware coffee set, pink, 6 cups, 6 saucers, lidded sucrier, cream jug and coffee pot. CONDITION REPORT: All pieces are allover lightly crazed. One cup is more significantly crazed than the others. Another cup has a significant crack running from the top lip down to the base. The lidded sugar basin has a small interior edge chip to the top of the body. The sugar basin is a little more crazed than the other pieces other than the cup already mentioned. All other pieces are in generally good order with no chips, no damage, no cracks, no repairs and no restoration.

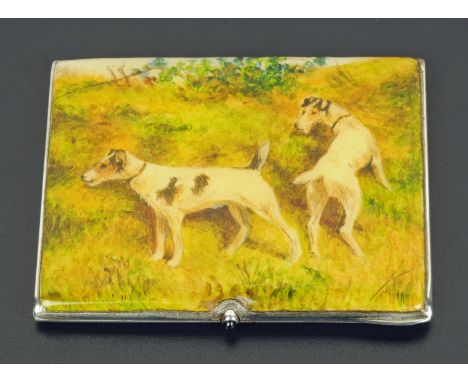

An Art Deco silver cigarette case, hallmarked. CONDITION REPORT: 87 mm x 69 mm. The outer case is a little dirty but in good structural order. There are no significant dents or scratches. The hinge is nice and tight and operates as it should. The clasp shuts correctly. The silver is scratched and worn around the indent above the opening button. It is difficult to tell but there may have been a repair here. There are some nibbles to the edges and corners of the enamel but no significant losses. There is no significant scratching or damage to the enamel surface.

An Art Deco "Bone China Scotia Salisbury" pattern tea set (20). CONDITION REPORT: One cup has a 1 cm hairline crack running from the top lip. All other pieces are in good order with no damage, no chips, no repairs and no restoration. There is some minor rubbing to the gilding and the pattern in places but no significant problems other than the small crack already mentioned.

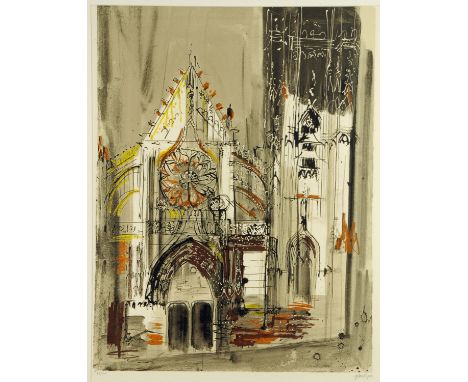

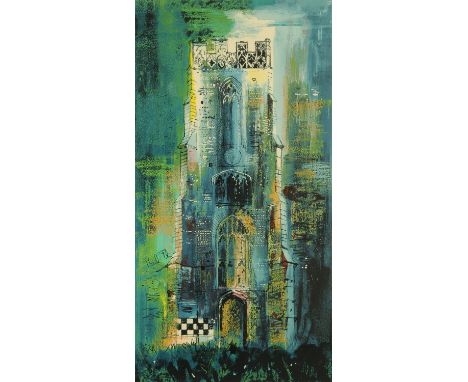

John Piper, artists proof screen print, 1986 "Stansfield". 86 cm x 45 cm, with copy of Christie's Contemporary receipt dated 1994 for £3,070 (see illustration). ARR CONDITION REPORT: The print itself is marked in pencil "AP" at the bottom left hand corner. It is not numbered. It is fully signed in pencil bottom right. The print appears to be in generally good condition. We can see no evidence of any discolouration or foxing. The print is fairly large and in our opinion requires remounting as it has sprung from the mount at the sides and top and is undulating. The print is under glass and has a softly rounded gilt frame. The mount is off white. Note - The receipt is from Christie's Contemporary Art Gallery, Dover Street, London.

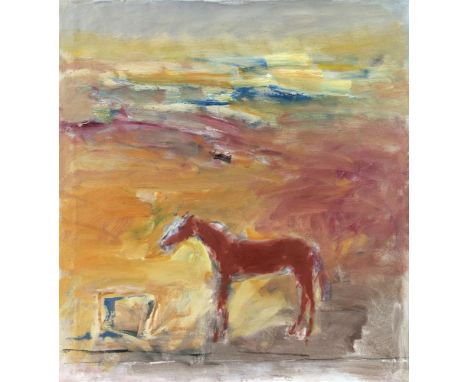

Basil Blackshaw HRHA RUA (1932-2016)Horse with Object IOil on linen canvas, 75 x 70cm (29½ x 27½'')Provenance: From the collection of the late Gillian Bowler.Exhibited: 'Basil Blackshaw Exhibition', Hendriks Gallery, September 1987, Catalogue No.23, where purchased.Horse and Object I, Horse and Object II, 1987Basil Blackshaw HRUA (1932-2016) was born in Glengormley but his family moved soon after to Boardmills, Co. Down. He studied at Art College in Belfast in the late 1940s. In 1951 Blackshaw was awarded a scholarship by the Committee for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts, to study in Paris. It was at this time that he encountered the work of a number of artists that were to have an enduring impact on his career. A major retrospective of Blackshaw’s work was held in 1974 at the Arts Council Gallery in Belfast, and another in 1995 was organised by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland. The latter was exhibited at the Ormeau Baths, Royal Hibernian Academy, Crawford Municipal Gallery, and a selection of the works travelled to the United States for a further tour. In 2001 he was the recipient of the Glen Dimplex Award for a Sustained Contribution to the Visual Arts. He exhibited at the Ulster Museum, Belfast in 2002 and a monograph was published on the artist by Eamonn Mallie in 2003. In 2012 the Royal Hibernian Academy in conjunction with the F.E. McWilliam Gallery organised a substantial retrospective of the artist’s work entitled ‘Blackshaw at 80’. He was a member of Aosdana, RUA and Associate Member of the RHA. Jude Stephens, Blackshaw’s model for his life studies commented that the artist was more than just a painter; he was a “traditional countryman who was rooted in rural life. He was someone who connected effortlessly with the natural world and he lamented the pace of change in much of rural Ireland, especially in the areas that he loved and knew best.” (The Irish Times, May 9, 2016)Denis Bradley, a close friend of the artist has remarked; “I think that nature was caught, it wasn’t just observed by you, it was in your bones, in your genes, in all of your breathing and living and being - the horses and the dogs and the fowl, everything that you painted, ultimately the human beings. It was not an observation or a study, it just came - the gift was there, you put it in the paint, you put it on the canvas. And for that thank you.” (The Irish Times, May 9, 2016)Blackshaw insisted he did not work in series and hence works that are linked have not been planned in sequence. They were often created separately with other subjects and genres intervening. ‘Horse and Object I’ and ‘Horse and Object II’ are however as close to a series as paintings can come. There is continuity in compositional structure, palette, representation, treatment and scale. They are interesting as a pair certainly but can also be appreciated individually. There is a sense of floating forms evident and a somewhat flattened canvas in both works. ‘Horse and Object I’ has a horse placed centrally in the lower ground of the canvas. He stands at ease before a square object in front of him. It is highly likely that the horse subject is Dolly (depicted in a later painting by name); one can see her chestnut hue, relatively slender form, white markings on her nose, and a sense of her white fetlocks. The artist is not aiming at an animal portrait but rather an explorative study of the two forms depicted. The surroundings to the forms are beautifully captured in pleasing pastel shades. The artist explained his compositional approach in his work to Brian McAvera; “I like…the feeling that it was a piece of work, an exploration, not a work made for exhibition.” (Irish Arts Review, Winter 2002, p67). In ‘Horse and Object II’ the compositional structure is very similar to its’ precedent yet the entire palette has been brightened and forms are now somewhat abstracted. The horse appears more grounded at the base of the canvas yet it is less life-like and more symbolic. This is due, largely, to the elongation of the horse’s face. In these works there is evidence of the artist’s method in creating his landscape compositions; ‘Blackshaw plays two and three dimensional space against each other to make a tense space like an imaginary rubber band between the foreground and background.’ (Frances Ruane, 1981). This tendency may come from the artist’s admiration of Cezanne as he ‘wanted, like him, to express the “pull and tension which is the whole life of art”. (Ruane, 1981). Mike Catto has also written about Cezanne’s influence; ‘The restraints and gradations which his palette achieved from 1967 onwards follows Cezanne’s advice to Emile Bernard “to begin lightly with almost neutral tones. Then one must proceed steadily climbing the scale and tightening the chromatics.” (Art in Ulster 2, 1977, p17). The early work of Sir Alfred Munnings his sketches and wood panels of horses were of interest to Blackshaw. Of greater importance, however, was Franz Marc’s ‘Grazing Horses IV’ (The Red Horses), 1911. It has been cited by the artist as ‘the only horse painting that had an influence on me.’ (Irish Arts Review, Winter 2002, p59). Indeed such an artist as Marc, through his expressionism, symbolism and primacy of colour, has had a clear impact on Blackshaw in these works and others where reference to the dominant colour enters the realm of the title; ‘Blue Nude’, ‘Brown Head’, ‘White Landscape’, and ‘Pink Dog’. If one were to select a painting that epitomised the closest tribute to Franz Marc it would be another horse painting entitled ‘Dolly’ 1989 which was executed a few years after the ‘Horse and Object’ works. Mercy Hunter, writing for an Arts Council exhibition catalogue in 1974 stated; ‘He especially admires Rothko because of the apparent ease of his achievement - “he has the pull and push to fill a great area; his sense of scale is everything.” However, he is not deceived by the seeming simplicity of Rothko’s works. He recognises draughtsmanship as a fundamental discipline…“you must be able to feel if a shape is right or wrong and every shape must have its own identity.” (Hunter, 1974). This sense of shapes and forms with their own inherent identity is certainly in evidence in the ‘Horse and Object’ paintings and that crafting of forms placed on the canvas is enhanced by the primacy of colour. Another definitive aspect to the works is their ability to bring a smile to the viewer’s face. They are pleasing both in terms of quirky composition and aesthetics; ‘One element is quite inescapable in many of these idiosyncratic paintings - deep and genuine humour, a quality often found in painters as private people (including, most definitely, Blackshaw himself) but surprisingly rarely in their work.’ (Brian Fallon in Blackshaw, 2003). One final observation on these works is their resistance to definitive classification in genre terms and this is in evidence throughout the artist’s oeuvre. Brian Fallon has written on Blackshaw’s unique approach and his propensity to go beyond defined genres; ‘There is also a large and very special category that stands outside all these and is entirely sui generis. It might roughly be defined as the special “Blackshaw subject,” meaning (very broadly) something quirky, unpredictable, occasionally ultra-personal or private, often based on sights that are familiar and everyday, or on quite non-descript things that just happen to have caught his eye or fancy and are re-shaped by his alert imagination. Some are almost epigrammatic in their visual wit, while others are lyrical or even poignant.’ (Blackshaw edited by Eamonn Mallie, Nicholson and Bass, Belfast, 2003) Marianne O’Kane Boal, April 2017

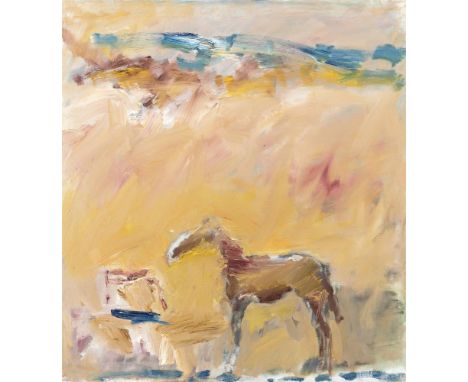

Basil Blackshaw HRHA RUA (1932-2016)Horse with Object IIOil on canvas, 75 x 70.2cm (29½ x 27½'')Provenance: From the collection of the late Gillian Bowler.Exhibited: 'Basil Blackshaw Exhibition', Hendriks Gallery, September 1987, where purchased; 'Basil Blackshaw Retrospective' travelling exhibition, Art Council of Northern Ireland; Ormeau Baths Gallery, Belfast, November/December 1995; Model Art and Niland Gallery, February 1996; the RHA Gallery, January 1997; Literature: Basil Blackshaw: Painter, by Brian Ferran 1995, Full Page illustration Pg114Horse and Object I, Horse and Object II, 1987Basil Blackshaw HRUA (1932-2016) was born in Glengormley but his family moved soon after to Boardmills, Co. Down. He studied at Art College in Belfast in the late 1940s. In 1951 Blackshaw was awarded a scholarship by the Committee for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts, to study in Paris. It was at this time that he encountered the work of a number of artists that were to have an enduring impact on his career. A major retrospective of Blackshaw’s work was held in 1974 at the Arts Council Gallery in Belfast, and another in 1995 was organised by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland. The latter was exhibited at the Ormeau Baths, Royal Hibernian Academy, Crawford Municipal Gallery, and a selection of the works travelled to the United States for a further tour. In 2001 he was the recipient of the Glen Dimplex Award for a Sustained Contribution to the Visual Arts. He exhibited at the Ulster Museum, Belfast in 2002 and a monograph was published on the artist by Eamonn Mallie in 2003. In 2012 the Royal Hibernian Academy in conjunction with the F.E. McWilliam Gallery organised a substantial retrospective of the artist’s work entitled ‘Blackshaw at 80’. He was a member of Aosdana, RUA and Associate Member of the RHA. Jude Stephens, Blackshaw’s model for his life studies commented that the artist was more than just a painter; he was a “traditional countryman who was rooted in rural life. He was someone who connected effortlessly with the natural world and he lamented the pace of change in much of rural Ireland, especially in the areas that he loved and knew best.” (The Irish Times, May 9, 2016)Denis Bradley, a close friend of the artist has remarked; “I think that nature was caught, it wasn’t just observed by you, it was in your bones, in your genes, in all of your breathing and living and being - the horses and the dogs and the fowl, everything that you painted, ultimately the human beings. It was not an observation or a study, it just came - the gift was there, you put it in the paint, you put it on the canvas. And for that thank you.” (The Irish Times, May 9, 2016)Blackshaw insisted he did not work in series and hence works that are linked have not been planned in sequence. They were often created separately with other subjects and genres intervening. ‘Horse and Object I’ and ‘Horse and Object II’ are however as close to a series as paintings can come. There is continuity in compositional structure, palette, representation, treatment and scale. They are interesting as a pair certainly but can also be appreciated individually. There is a sense of floating forms evident and a somewhat flattened canvas in both works. ‘Horse and Object I’ has a horse placed centrally in the lower ground of the canvas. He stands at ease before a square object in front of him. It is highly likely that the horse subject is Dolly (depicted in a later painting by name); one can see her chestnut hue, relatively slender form, white markings on her nose, and a sense of her white fetlocks. The artist is not aiming at an animal portrait but rather an explorative study of the two forms depicted. The surroundings to the forms are beautifully captured in pleasing pastel shades. The artist explained his compositional approach in his work to Brian McAvera; “I like…the feeling that it was a piece of work, an exploration, not a work made for exhibition.” (Irish Arts Review, Winter 2002, p67). In ‘Horse and Object II’ the compositional structure is very similar to its’ precedent yet the entire palette has been brightened and forms are now somewhat abstracted. The horse appears more grounded at the base of the canvas yet it is less life-like and more symbolic. This is due, largely, to the elongation of the horse’s face. In these works there is evidence of the artist’s method in creating his landscape compositions; ‘Blackshaw plays two and three dimensional space against each other to make a tense space like an imaginary rubber band between the foreground and background.’ (Frances Ruane, 1981). This tendency may come from the artist’s admiration of Cezanne as he ‘wanted, like him, to express the “pull and tension which is the whole life of art”. (Ruane, 1981). Mike Catto has also written about Cezanne’s influence; ‘The restraints and gradations which his palette achieved from 1967 onwards follows Cezanne’s advice to Emile Bernard “to begin lightly with almost neutral tones. Then one must proceed steadily climbing the scale and tightening the chromatics.” (Art in Ulster 2, 1977, p17). The early work of Sir Alfred Munnings his sketches and wood panels of horses were of interest to Blackshaw. Of greater importance, however, was Franz Marc’s ‘Grazing Horses IV’ (The Red Horses), 1911. It has been cited by the artist as ‘the only horse painting that had an influence on me.’ (Irish Arts Review, Winter 2002, p59). Indeed such an artist as Marc, through his expressionism, symbolism and primacy of colour, has had a clear impact on Blackshaw in these works and others where reference to the dominant colour enters the realm of the title; ‘Blue Nude’, ‘Brown Head’, ‘White Landscape’, and ‘Pink Dog’. If one were to select a painting that epitomised the closest tribute to Franz Marc it would be another horse painting entitled ‘Dolly’ 1989 which was executed a few years after the ‘Horse and Object’ works. Mercy Hunter, writing for an Arts Council exhibition catalogue in 1974 stated; ‘He especially admires Rothko because of the apparent ease of his achievement - “he has the pull and push to fill a great area; his sense of scale is everything.” However, he is not deceived by the seeming simplicity of Rothko’s works. He recognises draughtsmanship as a fundamental discipline…“you must be able to feel if a shape is right or wrong and every shape must have its own identity.” (Hunter, 1974). This sense of shapes and forms with their own inherent identity is certainly in evidence in the ‘Horse and Object’ paintings and that crafting of forms placed on the canvas is enhanced by the primacy of colour. Another definitive aspect to the works is their ability to bring a smile to the viewer’s face. They are pleasing both in terms of quirky composition and aesthetics; ‘One element is quite inescapable in many of these idiosyncratic paintings - deep and genuine humour, a quality often found in painters as private people (including, most definitely, Blackshaw himself) but surprisingly rarely in their work.’ (Brian Fallon in Blackshaw, 2003). One final observation on these works is their resistance to definitive classification in genre terms and this is in evidence throughout the artist’s oeuvre. Brian Fallon has written on Blackshaw’s unique approach and his propensity to go beyond defined genres; ‘There is also a large and very special category that stands outside all these and is entirely sui generis. It might roughly be defined as the special “Blackshaw subject,” meaning (very broadly) something quirky, unpredictable, occasionally ultra-personal or private, often based on sights that are familiar and everyday, or on quite non-descript things that just happen to have caught his eye or fancy and are re-shaped by his alert imagination. Some are almost epigrammatic in their visual wit, while others are lyrical or even poignant.’ (Blackshaw edited by Eamonn Mallie, Nicholson and Bass, Belfast, 2003) Mariann

Basil Blackshaw HRHA RUA (1932-2016)Head of a TravellerOil on canvas, 61 x 45cm (24 x 17¾'')Signed and dated (19)'84 versoProvenance: From the collection of the late Gillian Bowler.Basil Blackshaw HRUA (1932-2016) was born in Glengormley but his family moved soon after to Boardmills, Co. Down. He studied at Art College in Belfast in the late 1940s. In 1951 Blackshaw was awarded a scholarship by the Committee for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts, to study in Paris. It was at this time that he encountered the work of a number of artists that were to have an enduring impact on his career. A major retrospective of Blackshaw’s work was held in 1974 at the Arts Council Gallery in Belfast, and another in 1995 was organised by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland. The latter was exhibited at the Ormeau Baths, Royal Hibernian Academy, Crawford Municipal Gallery, and a selection of the works travelled to the United States for a further tour. In 2001 he was the recipient of the Glen Dimplex Award for a Sustained Contribution to the Visual Arts. He exhibited at the Ulster Museum, Belfast in 2002 and a monograph was published on the artist by Eamonn Mallie in 2003. In 2012 the Royal Hibernian Academy in conjunction with the F.E. McWilliam Gallery organised a substantial retrospective of the artist’s work entitled ‘Blackshaw at 80’. He was a member of Aosdana, RUA and Associate Member of the RHA. ‘Head of a Traveller’ painted in 1984 is quite different from much of Blackshaw’s figurative work and portraiture. This work demonstrates a relatively broad palette compared to that generally found in the artist’s practice. It is almost as if Blackshaw has sculpted the head from earth and clay, such are the modelling marks that could have as easily been made with the hands; fingers and thumbs, as with the brush. The subject’s visage is characterful in its rendering; he has one blue eye, one brown, a prominent nose, dark shadowed chin and long unkempt jet-black hair. The painting is powerful and memorable and it portrays a depth of character in the man portrayed that clearly left an intense impression on the artist. In 1985, Mike Catto wrote; ‘The superb Heads of Travellers were far from lovely - no stage Irish rustics these; instead the artist gave us stripped down direct faces. There was an effect almost of a blurred out-of-focus photograph in these faces, a sensation which has echoed in many of his figures over the years.’ (Aer Lingus Cara Magazine, 1985). While Catto is certainly accurate in his description of this group of works, this work ‘Head of a Traveller’ stands apart from the others. It gives the impression, for a number of reasons, that it was the first portrait the artist produced on this theme; It is more detailed, expressionist, and demonstrates a broader palette; although the man’s face is turned to the side, his eyes look directly at the viewer in a confrontational stare; in terms of connection of expression, it is akin to Roderic O’Conor’s ‘Breton Peasant Woman Knitting’ 1893, in the intensity of execution and striped treatment of the corduroy jacket the traveller wears - this handling contrasts with that of the other works in the group that feel closer to Barrie Cooke in palette and finishing. Indeed it stands apart to such a degree that it seems closer to other works by Blackshaw than these portraits on the same subject. Dr Fionna Barber felt that; ‘The expressionist brushstroke never totally describes the faces of his sitters; rather it suggests a pictorial equivalent to their presence.’ (F.E. McWilliam Gallery, 2012, p28). When writing about an earlier work entitled ‘The Field’ by Blackshaw, Brian Fallon commented on the ‘uninhibited brushwork and almost Expressionist vehemence’ of the painting. (Obituary, The Irish Times, May 6, 2016). These attributes can also be seen in ‘Head of a Traveller’ painted some thirty years later. One of the defining aspects of Blackshaw’s work is the inherent challenge of the struggle of articulation. He was an artist who embraced this struggle as necessary and fundamental to the process; ‘...This is a man who has learnt that he was once too close to his subject matter; a man who would love to be an abstract painter but is not; a man who can make scale, surface and the emotional temperature of colour coalesce; a man who has learnt to avoid the slick or clever brushstroke, or the purely descriptive brushstroke in favour of a painter’s marks.’ (Brian McAvera, Irish Arts Review, Winter 2002, p59). This portrait of an unnamed traveller is the epitome of the coalescence of ‘scale surface and the emotional temperature of colour’ and it has certainly been informed by the artist’s vision and his unique ‘painter’s marks.’Marianne O’Kane Boal, April 2017

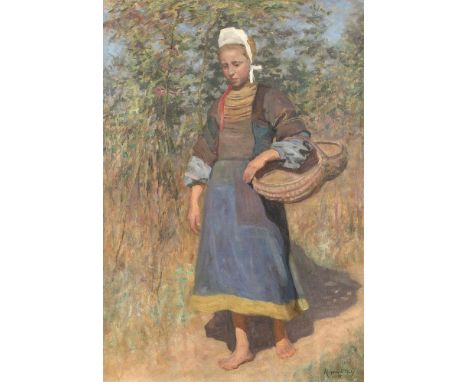

Aloysius O'Kelly (1850-1929)Portrait of a Young Breton GirlOil on canvas, 91.5 x 63.5cm (36 x 25'')Signed and dated 1905Exhibited: Re-orientations, Aloysius O’Kelly: Painting, Politics and Popular Culture, Hugh Lane Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin, 1999-2000, no 25.Literature: Niamh O’Sullivan, Re-orientations, Aloysius O’Kelly: Painting, Politics and Popular Culture, Hugh Lane Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin, 1999-2000; and Aloysius O’Kelly: Art, Nation, Empire, Field Day, 2010.In the late nineteenth century, O’Kelly embraced increasingly naturalistic concerns, but this iridescent painting is more modernist than usual from O’Kelly. The young girl is treated as an integrated element in the landscape, saturated with hot colour. Nineteenth-century paintings of Bretons show women wearing distinctive white linen coiffes and wide collars, dark skirts, waisted bodices, embroidered waistcoats, and heavy wooden sabots, but this modern Mademoiselle is informal in her bare feet, and modern in her dress, showing the evolution of peasant life in Brittany at the turn of the twentieth century. Niamh O’Sullivan May 2017

Basil Blackshaw HRHA RUA (1932-2016)Standing NudeOil on linen canvas, 90 x 70cm (35½ x 27½'')Signed and numbered No. 3 versoProvenance: From the collection of the late Gillian Bowler.Exhibited: 'Basil Blackshaw Exhibition', the Hendriks Gallery, September 1987, Catalogue No. 20, where purchased.Basil Blackshaw ‘Nude’ Studies Lots 109,110 and 112Mike Catto has written; ‘The nudes of Basil Blackshaw have a certain air of detachment about them.’ (Art in Ulster 2, 1977, p43). I disagree with this interpretation because although I can see where such a reading comes from there is too remarkable a degree of connection evident between artist and model in these nude representations. The sense of distance or detachment is at odds with the impact of the works. They have been consciously embodied by Blackshaw in this manner. He is a strong portraitist and is adept at capturing likenesses but his nudes are not executed in this vein. In these it is the figure’s moment and opportunity to shine through in terms of expression. These nudes are faceless, nameless, yet paradoxically full of character. They are collectively reliant on their expressive poses and the artist’s treatment of paint and compositional structure. Blackshaw is definite in his approach; “…I want to avoid association with the subject. I want it to be a purely visual experience for the viewer…I want it to please the eyes rather than bring up associations in the mind. When I paint a nude I don’t want them to see a girl thinking or sitting, I want it be just a figure. I like the way Baselitz turned his figures upside down, when you see a man eating an orange, turn it round and it becomes something else. I wish I’d thought of it.” (‘Afterwords’, Ferran, 1999, p128). Brian Ferran has noted; ‘Although his model is before him, his more important associations are the previous twenty paintings which he has made of the same model…These are densely complex paintings which possess personality and a dynamism of their own.’ (Ferran, 1999, p122). The artist has commented; ‘I want to be divorced a bit from the actual subject; not to make a replica but to make an equivalent.’ (McAvera, IAR, 2002). The most insightful and detailed assessment of the artist’s approach, is however, captured by the person closest to the subject, his life model Jude Stephens; ‘His approach was to create a representative image, almost totally destroy it, and then recreate it. Within hours or even minutes of my departure, I knew that he would return to the studio and obliterate the image, for only when I left could he produce the painting for which he strove. In a sense the essence he sought only existed in his memory. He often apologised about this pattern of thesis, antithesis and synthesis, reassuring me that he needed me to sit for him even though the resulting work would inevitably meet with rough treatment, because without an image to destroy there could be no image to recreate.’ (Jude Stephens in Ferran, 1999, p85). ‘Reclining Nude’ has an elemental, almost archaeological feel to it. The figure occupies the composition but in a pose that suggests movement and a sense of becoming. Her form emerges from the left of the page and stretches back towards the right. The cut-off composition emphasises the sense of a found or emerging form. Her feet are beyond the confines of the page as is her left hand. Her facial features see little delineation, her hair is akin to a dark shadow extended behind her head and indeed her entire form is captured only to the point of sufficient suggestion of presence and not beyond. Nevertheless the figure does however have a strong manifestation even in this elemental existence. The painting is powerful and dynamic within its severely limited palette range. It is at once linked to the classical tradition and yet thoroughly modern. ‘Blue Nude’ 1985 was painted the same year and it also possesses a power of mastery of the figure. The blue of the title is the dominant colour with the background a deep midnight blue which casts its hue upon the model. Marianne O’Kane Boal, April 2017

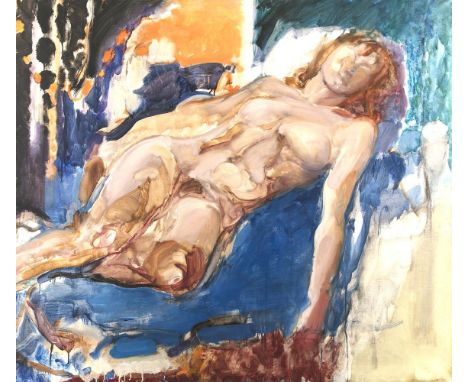

Barrie Cooke HRHA (1931-2014)Blue NudeOil on canvas, 105 x 120cm (41¼ x 47¼'')Inscribed by the artist verso 'Blue Nude, Barrie Cooke 85'Provenance: With Hendricks Gallery, label verso, September 1992, No. 3; Gillian Bowler.Exhibited: The Hendriks Gallery, 1985, where purchased; 'Barrie Cooke Exhibition', Haags Gemeente Museum, The Hague, Holland, Tentoonastelling 1992, Catalogue No. 3.Literature: 'Barrie Cooke' by Aidan Dunne, 1986, Douglas Hyde Gallery, detail front cover illustration, illustrated again p.119 under title 'Blue Figure'.Barrie Cooke was one of the dominant figures in Irish painting throughout the 1960-90s. Born in Cheshire, in England, he spent his teenage years in the United States and studied art history and science at Harvard before coming to live in Ireland in 1954. Apart from time spent studying under Oskar Kokoschka in 1955, and his extended trips to Borneo, New Zealand, Malaya, Lapland and other places, he has lived in counties Clare, Kilkenny and Sligo for most of his adult life. ‘Blue Nude’ is one of many nudes painted by Cooke although the artist is generally seen as a landscapist with a passionate concern for saving nature from the devastating consequences of human intervention. His paintings of the female body, like his portraits of friends, can be seen as a continuation of his landscapes. When he painted a portrait of his friend, the American writer, Tess Gallagher, she wrote an account of the process, which has him saying ‘for me you will simply be a landscape’. That this is clearly true too, of his female nudes, is evident in his earliest ventures into the genre, begun when he was living in Clare in the 1950s and early 60s. There he painted the figures of women emerging from the bare landscape of the Burren, making the linkage between the earth and the people who occupy it appear seamless. His famous Sheila-na-Gig paintings, in which the nude is built up, in three dimension from clay and fused with the painted ground were landmark works in this genre.‘Blue Nude’ shows the consistency of this motif in his art and, although painted in 1985, bears a remarkable resemblance to earlier nudes from the early 1960s in the Gordon Lambert Trust at the Irish Museum of Modern Art and in other collections. What they have in common is what Seamus Heaney referred to as Cooke’s ‘aqueous vision’, which makes the female body appear to bend and flow with the contours of the landscape or the barely defined physical surroundings of the interiors in which they are sometimes placed. The palette of strong blues and oranges also remains consistent.Cooke loved to work directly onto raw canvas, allowing the paint to seep into it and stain it like a river caressing its banks, creating a strong sense of fluidity rather than precise finish. For that reason, ‘Blue Nude’ should not be understood in the usual sense of a study for a more complete painting but rather as an end in itself, in which the body is surrounded by a very sketchy background, which has references both to the landscape and to an interior setting. The fact that it was intended as a completed painting rather than simply a study, like so many of his nudes, is borne out by the fact that the painting was included in his retrospective exhibition at the Gemeentemuseum at the Hague in 1992.Barrie Cooke was a significant influence, not just on younger artists in Ireland, but also on the context for making and showing art to the wider public. He was a founding member of the Independent Artists group in 1961 and, successively, an active member of the boards of the Butler Gallery, where he had a considerable role in the shaping of the Kilkenny Arts Festival, and of the Douglas Hyde and Model and Niland Galleries in Dublin and Sligo respectively. He was also a founder member of Aosdána and through his wide international connections, an important transmitter of external influence on Irish art.Catherine Marshall, April 2017

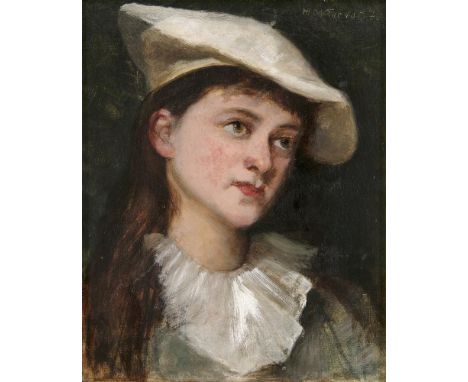

Helen Mabel Trevor (1831-1900)A Little French GirlOil on canvasSigned. Title inscribed on label versoBorn in Loughbrickland, Co. Down in 1831 Helen Mabel Trevor showed a talent for drawing as a child, and her father Edward Hill Trevor of Lisnageard House, set up a studio for her. In the 1850s she exhibited portraits and animals studies at the Royal Hibernian Academy.In her forties, after the death of her father, she began to study art formally at the Royal Academy Schools, London, 1877-1881. Then began a long period of travel and residence on the Continent with her sister Rose. They visited Brittany and Normandy c.1880-1883, working variously at the artists’ colonies of Pont-Aven, Douarnenez and Concarneau in Finistere, and at Trouville. Helen painted several studies of elderly women and children in a Realistic manner, and landscapes in the open air. The Trevor sisters lived in Italy, 1883-c.1889, visiting Florence, Assisi, Perugia, Venice and Rome, Helen copying Old Master paintings in museums, and painting genre scenes of Italian life.The Trevors moved to Paris in 1889, and this became their base during the 1890s. Now nearly sixty, Helen attended classes in the ateliers of Carolus-Duran and Jean-Jacques Henner, and in 1894 of Luc-Olivier Merson. She painted in the artists’ colony of St. Ives in Cornwall, c.1893 and Concarneau, in Brittany 1895-96, and at Antibes in the South of France, 1897.Trevor exhibited regularly at the RHA and at the Paris Salon, 1889-1899, gaining honourable mention there in 1898. After her death in Paris in 1900, two of her paintings, of Breton or Normandy peasant subjects, were bequeathed to the National Gallery of Ireland, and Rose presented a Self-Portrait by Helen. Another Breton painting ‘The Young Eve’ is in the collection of the Ulster Museum, Belfast.

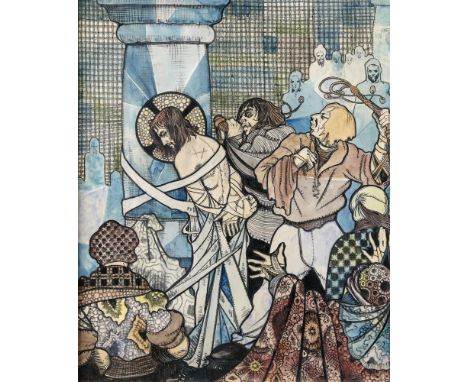

Christopher Campbell (1908-1972)The Flaying of JesusMixed media on paper, 84 x 68cm (33 x 26¾'')Signed and dated 1930Exhibited: Royal Dublin Society, National Art Competition First Prize Class 35; 'Christopher Campbell Retrospective Exhibition', the Neptune Gallery, Catalogue No.53 (illustrated in catalogue).

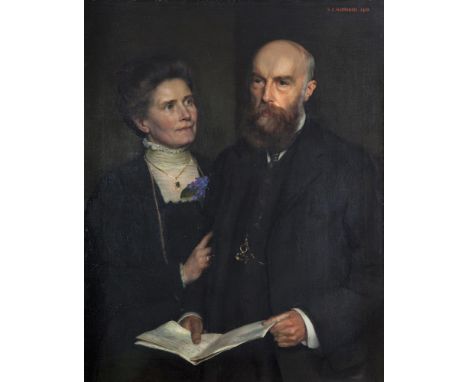

Sarah Cecilia Harrison RHA (1863-1941)Blayney R.J. Balfour and Madeline, his Wife, of Townley Hall, DroghedaOil on canvas, 91 x 73cm (35¾ x 28¾)Signed and dated 1910Exhibited: The RHA Annual Exhibition 1911, Cat. No.26Provenance: The Townley family by descent and sold by them through The Gorry Gallery 1994. Later sold Adam’s Important Irish Art Sale September 2002 Cat. No. 65 where purchased by current owners.This portrait used to hang in Townley Hall Co. Louth . The sitters are Blayney R. Townley Balfour and his wife Madeline. Madeline was the daughter of John Kells Ingram LLD Vice-Provst of TCD. Sarah C. Harrison was one of the leading portrait painters of her day. She was also a great campaigner and created history as being the first woman to be elected a member of Dublin Corporation. She was an early fighter for women’s rights and campaigned for the cause of Dublin’s poor and had an office in 7 St. Stephens Green where she weekly listened to their grievances. She was a well known campaigner for the provision of a Modern gallery for The Lane pictures. Hugh Lane had presented her 1908 portrait of Thomas and Anna Haslam, pioneers of the Irish suffrage movement, to Dublin’s Municipal Gallery.

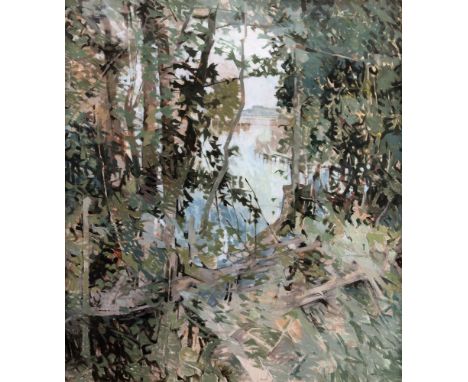

Terence P. Flanagan PPRUA RHA (1929-2011)Portora for Tony Flanagan (1987)Oil on canvas, 112 x 106cm (44 x 41¾'')SignedProvenance: From the collection of the late Gillian Bowler.Exhibited: T.P. Flanaghan RHA PPRUA 25 Years with the Hendriks Gallery Exhibition, Hendriks Gallery Dublin, June 1987, where purchased; “T. P. Flanagan, Retrospective Exhibition”, Ulster Museum, Belfast; Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin; Fermanagh County Museum, Enniskillen, Catalogue No.84 in each case.Literature: “T. P. Flanagan, Retrospective Exhibition, Belfast, Dublin and Enniskillen” by Dr SB Kennedy, picture illustrated on front cover of the catalogue; “T. P. Flanagan: Painter of Light and Landscape”, London, Lund Humphries, 2013, reproduced in colour pp. 130, 131. The composition is important in Flanagan’s work for it confirms the movement towards a calligraphic technique that came to dominate his painting. This was a development Aidan Dunne noted in the Sunday Tribune (14 June 1987): ‘Flanagan is a superb technician’, he said, ‘a shadow boxer of a painter whose ghostly images find their way on to the surface in a fusillade of jabs and darts. The calligraphic maze of brushstrokes continually threatens to collapse into abstraction, but it is invariably rescued by the painter’s strong, instinctive grasp of his subject, a kind of privileged link with the landscape described’. His ‘problem,’ said Ciaran Carty in the same issue of the paper ‘is that [he] can never paint a thing at the time. [He’s] got to let it lie in the imagination and marinate’. Recalling Flanagan’s childhood memories of travelling by train from Enniskillen to Sligo, Carty said that he had ‘loved the sensation of momentarily seeing something from the window only for it to pass out of vision never to be seen again’. Brian Fallon also praised the exhibition in the Irish Times (6 June1987), although he had reservations about the artist’s developing style. ‘Flanagan’s early style’, he said, ‘was refined, understated and spare, almost Oriental’, but he had moved away from it in the last decade to become ‘lusher, prettier and also more conventional’. Nevertheless, he said, many works ‘stand well above that level’. To Dorothy Walker, in the Independent (12 June 1987), the artist’s ‘light fluid style’ was ‘immediately recognizable, and she thought there was ‘more substance than usual in the oil paintings, almost a sense of urgency in the familiar rapid brush strokes’. The subject of the picture is Lower Lough Erne near Portora Royal School.Dr SB Kennedy May 2017

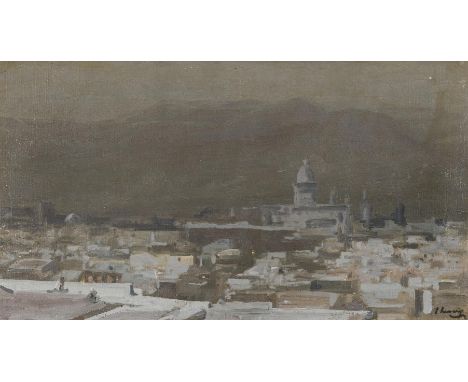

Sir John Lavery RA RHA RSA (1856-1941)Moonlight, Tetuan, MorrocoOil on canvas, 36 x 63.5cm (14¼ x 25'')Signed, inscribed with title and dated 1911 versoProvenance: C.W. Kraushaar, by whom donated to the Toledo Museum of Art; their sale Sothebys, 16th May 2008, where purchased by current owner.Literature: 'The Toledo Museum of Art: European Paintings', 1976, plate 341, illustrated page 92.From the 1830s North Africa and the Middle East became places of artistic pilgrimage, but while painters such as Lewis, Lear and Holman Hunt preferred the eastern Mediterranean, in Lavery's era an instant Orient was to be found by simply crossing the Straits of Gibraltar. Where Orientalist painters concentrated upon narrating the Eastern way of life, the rituals of the Mosque and the Harem, Lavery's generation looked to this environment for its colour.Lavery's first visit to Morocco took place in 1891, at the instigation of his friends, the Glasgow artists Arthur Melville and Joseph Crawhall. After almost annual visits, in 1903 he bought Dar-el-Midfah ('the House of the Cannon', for a half buried cannon in the garden), a small house in the hills outside Tangier which he continued to visit with his family over the next 20 years. It has been claimed that for Lavery the strong light, cloudless sky, white walls and bright colour of Arab dress helped to cleanse his eye after sustained periods of studio portraiture. Within a few years of visiting Morocco for the first time, the light sable sketching of his Glasgow period gave way to a richer and more sensuous application.Lavery exhibited Tetuan, Moonrise in The Leicester Galleries exhibition Cabinet Pictures by Sir John Lavery in 1904, Cat. No. 38, so is likely to have travelled there in 1903/1904. Again, in the spring of 1906, Lavery took an overland expedition to Fez together with Walter Harris and Cunninghame Graham and travelled along the coast to Tetuan before travelling inland to Fez. Lavery undertook several studies of the market place at Tetuan, the camp outside the city walls and this nocturne painted on the outskirts of the town. Although dated 1911, Kenneth McConkey suggests he is unlikely to have visited Tetuan in that year due to the rising tensions in Morocco (even on their 1906 visit they were accompanied by 13 armed guards) and so it is likely that Lavery painted this based on the sketch exhibited in 1904, or another sketch from his trip in 1906, and just finished this work in 1911. Lavery executed quite a number of nocturne views during his time in Tangiers.Kenneth McConkey has described this work On one of these occasions the Port clothed in Moonlight, took on an air of mystery which appealed to Lavery's acute sensitivity to colour and toneWe are grateful to Prof. Kenneth McConkey whose many writings on Sir John Lavery formed the basis of the catalogue entry.

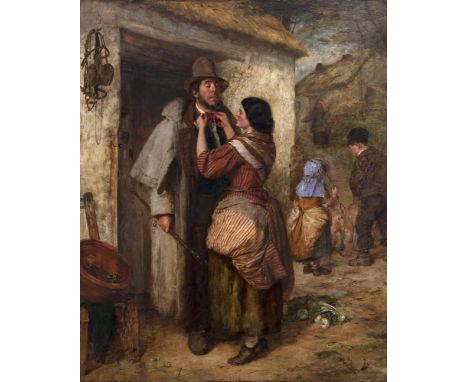

Erskine Nicol RSA ARA (1825-1904)Preparing for Market DayOil on canvas, 103 x 83cm (40½ x 32¾'')Signed and dated 1867Although born and living the majority of his life in Scotland, Nicol had an enduring interest in Ireland and Irish society. He first visited in 1846 and stayed for four years and returned regularly over the course of his artistic career. Nicol established a studio for his work at Cloncave in County Westmeath. As a mid-19th century artist, Nicol inhabits an interesting period in which there was a gradual shift away from Romantic painting to what would become in a more concrete sense towards the latter end of the century, a ‘Realist’ style. However, an issue, which pervaded Irish art well into the twentieth century, was the lack of any homogenous school of Irish painting. There had always been a tension between the way Irish people viewed themselves and the way in which they were viewed by others from the outside. A difficulty made more apparent alongside the emerging realist style as there was a tendency for British painters to present Irish rural life through a biased and sentimental lens. While Nicols is best known for his depictions of the poor and marginalised members of Irish society - particularly pertinent since his arrival coincided with the Great Famine (1845-52) which devastated the country- there was a fine line between bearing witness to the plight and struggles of those individuals and pandering to a stereotype of the ‘stage Irishmen’ through a Victorian moralising lens. Fairs and markets were a crucial element of social and commercial life of Irish towns for centuries. The occasion is apparent in the fashion of the gentleman as he steps out the door wearing his top hat and inverness outer coat. Nicol draws our attention to certain accents of details, the red neckerchief, the striped train of the mother’s dress, blue child’s bonnet or the pile of turnips on the ground. These vegetables belies a more rural character to the image balanced by the two small children leading the pigs to their pen or the woman in background of the image shielding her face from the sun while carrying a large basket in one hand, presumably on her way to work in the fields. In poor farming families the luxury of shoes was reserved for the men who needed them while working with the livestock. However, in this image none of the family members is barefoot; this scene is more of a light-hearted and cheerful depiction of Irish social rituals. Although the location is not indicated, Donnybrook’s annual fair was infamous for attracting artists to record its lively and at times raucous spirit. Nicols often focused on these less salubrious aspects in his paintings but in this instance the present example reflects a more subtle and considered reflection capturing a tender moment of domestic life. Niamh Corcoran

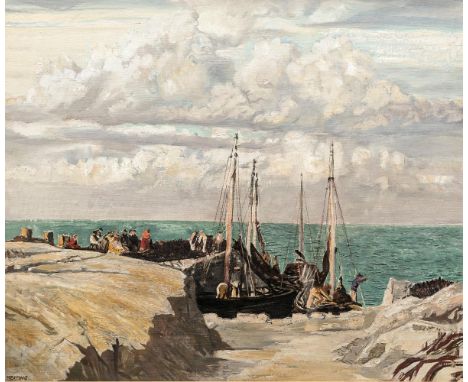

Sean Keating PRHA HRSA HRA (1889-1978)The Turf Quay, AranOil on canvas board, 61 x 76cm (24 x 30'')SignedProvenance: Important Irish art Sale, these rooms, 27th May 1998, where purchased by current owner.With a keen eye for the detail of the weather conditions, seen in the quiet clouds and, in the tranquil sea, The Turf Quay, Aran is an excellent example of the type painting for which the artist, Seán Keating, became very well-known from the mid-1930s onwards. There was no turf on Aran; the fuel had to be collected from larger boats anchored off shore, a job that could only be done when the weather at sea was suitably calm. Dealing with the turf was highly labour intensive. Once off loaded from the local boats, it was piled into individual wicker baskets known as creels, which were then saddled to the backs of the inhabitants, or donkeys, for transportation to local homesteads.Taking advantage of the good weather, the turf boats in The Turf Quay, Aran, have returned from deeper seas. Local men busily unload the turf onto the quayside, while both men and women gather around the piles ready to fill their creels, three of which lie empty to the left of the image. Yet, rather than illustrating the chatter and clamour of the busy scene, Keating kept his distance, and as a result, his viewers are encouraged to observe the contemplative, ritualized aspects of island life, in which each member of the community is absorbed in the work at hand, and all are testament to the spiritual and social value inherent in hard work and, in working together.The Turf Quay, Aran, is similar in composition and style to a series of paintings that the artist made from the mid-1930s to the early 1940s, which, although observed from life, were composed using film footage as an aid memoir. Indeed, the viewpoint that Keating adopts in The Turf Quay, Aran creates a cinematic atmosphere, reminding the twenty-first century viewer of the artist’s friendship with filmmaker, Robert Flaherty, which developed when the latter lived on the islands while filming scenes for Man of Aran in the early 1930s. Dr Éimear O’Connor HRHA

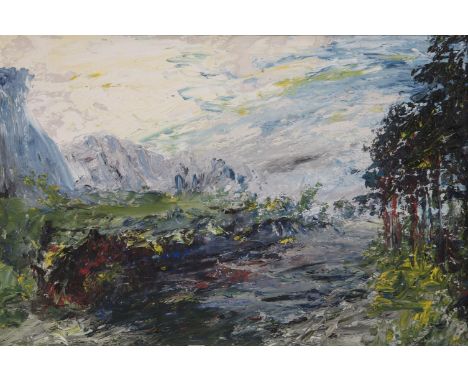

Jack Butler Yeats RHA (1871-1957)Early Morning, Cliffony (1941)Oil on panel, 23 x 36cm (9 x 14¼'')SignedExhibited: RHA Annual Exhibition 1942, Catalogue No.187; Jack B. Yeats Exhibition, York City Art Gallery, 1960, presented as part of 'The York Festival', Catalogue No. 22; Images in Yeats Exhibition, Cente de Congrés, Monaco June 1990; The National Gallery of Ireland July 1990, Catalogue No. 26.Provenance: Sold to Mr & Mrs Michael Burn in 1942; and later in the collection of Miss Harnett; sold in Christie’s Irish Sale, Dublin, May 1989, where purchased; from the collection of the late Gillian Bowler.Literature: Jack B. Yeats: An appreciation and Interpretation by Thomas MacGreevy, Dublin 1945, p.31/2; Images in Yeats (1990) by Hilary Pyle, illustrated p.53, plate 26.Jack B. Yeats: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Oil Paintings, by Hilary Pyle, Andre Deutsch 1992, Catalogue No.518, p.477Yeats painted this small vibrant work in 1941 at the beginning of one of the most productive decades of his career. It depicts the countryside near the coastal Sligo town of Cliffony. According to Hilary Pyle, the view is looking eastwards away from the town at the dramatic Dartry mountain range which includes such famous peaks as Ben Bulben and Truskmore. The Bunduff river, which marks the border between Connaught and Ulster, is surging through the foreground. On the extreme rights its banks are lined with saplings. The paint is applied with great variety of technique, from the sketchy dark leaves of the trees to the sculptured cliff faces of the mountains. The palette contrasts pale blues and mauves with bright reds and yellows. This and the dynamic way in which the forms are depicted creates an animated surface, suggestive of the energy of nature. The elements of rocky mountain, open sky and fast-flowing river are subtly demarcated by the lush colours of the grass, trees and vegetation of the land. The countryside of north Sligo appears as a fluid, constantly changing vista. Pyle has suggested that Yeats made pure landscapes like Early Morning, Cliffony, as an alternative and perhaps as a respite from his creation of large-scale fantasy works such as Tinkers Encampment, Blood of Abel, (1940, Private Collection) and Two Travellers, (1943, Tate). The production of both kinds of painting flourished in his oeuvre of the 1940s. Both refer to the West of Ireland and particularly to Sligo. The latter was closely connected to Yeats’s childhood, the memories of which formed a crucial source for his painting at this later stage in his life. Sligo also forms the backdrop to the myths and legends of ancient Ireland such as those associated with Queen Medbh and Diarmuid and Grainne whose stories are connected to specific locations in the Dartry mountains. Landscapes such as Early Morning, Cliffony were painted in the studio from memory, sometimes aided by earlier sketches made on the spot. They can be understood as settings for human events and affairs both real and imaginary. But as Thomas MacGreevy put it, ‘With Yeats, the landscape is as real as the figures. It has its own character as they have theirs’.Early Morning, Cliffony, with its yellow flecks of morning light and the vibrancy and movement of the foliage, sky and water is an important example of this type of painting. It expresses the energy and drama of this terrain as the artist remembers it and recreates it. On seeing the work at the RHA in 1942, MacGreevy described it as a small gem of pure landscape. It featured in the 1990 exhibition, Images in Yeats, shown at Monaco and the National Gallery of Ireland, as a quintessential example of Yeats’s pure landscape paintings.

Jack Butler Yeats RHA (1871-1957)Jack B. Yeats: A catalogue Raisonné of the oil paintings by Hilary Pyle London: André Deutsch, 1992. Three volumes, 1856pp with 1822 illustrations, 111 in colour. Cloth in a slipcase fine unopened condition. Definitive catalogue raisonné of Ireland's greatest painter, bringing together every known oil painting by Yeats, providing further documentary illustrations where appropriate and citing all relevant sources and influences. No. 399 from an edition limited to 1500, a must have for anyone interested in the history of Irish art and work of Jack B. Yeats. Mint unopened condition.

Patrick Collins HRHA (1911-1994)The BathOil on panel, 60 x 120cm (23½ x 47¼'')Signed lower left; inscribed with title versoProvenance: From the collection of The Dubliners' singer, the late Luke Kelly, and acquired by Gillian Bowler from the singer's partner, Madeleine Seiler, who was then a neighbour on Dartmouth Square. It is thought that Luke Kelly acquired the work from his friend, Paddy Collins, directly, so this is the first public viewing of this important work.Patrick Collins once described Paul Henry, whom he greatly admired, as a ‘modest man who painted Ireland like an Irishman’. Collins himself came to be prominently identified as someone who painted Ireland, its land and less frequently, its people, like an Irishman. He had a keen sense of mission to identify some kind of essential qualities of ‘Irishness’ or ‘Celticness’ and to express that in a visual language that was distinctive and recognisable. The writer Brian Fallon thought of him as having been ‘wholly original from the start’ (1), a view that Fallon held despite him and others regularly asserting that Collins was the Sligo inheritor of Jack B. Yeats’s legacy.What Fallon and others, especially Collins’ biographer, Frances Ruane, particularly admired was the artist’s ability to combine a sense of that Irishness with modernism at a time when those two qualities appeared almost contradictory. Collins is best known for his dreamy, nearly monochrome landscapes, which are usually bathed in soft grey light. The figurative elements in these landscapes, traveller families, animals, birds, the occasional church spire or ancient stones, hover out of mists of paint as if time has blended them with the overall atmosphere of the country. Yet Collins also painted the female nude, and was one of the first Irish artists to popularize the genre in his own country. Not only that, his early gestures in this field reveal an element of defiance in the face of Ireland’s Catholic prudishness in the 1960s. Thus 'Nude 1', from the Basil Goulding collection in the Butler Gallery, Kilkenny, shows the figure peeling off the last of her clothes for the artist, as if to say, it is the duty of art to reveal all. The figure is outlined more boldly than is typical in Collins’ work but is set into his trademark blue-grey, halo like ground.'The Bath', is relatively unusual however, not in the use of the nude, but in its open homage to the work of Pierre Bonnard, and in particular Bonnard’s 'Nude in the Bath', 1937 in the Petit Palais, Paris, which Collins would have seen when he lived in France in the 1970s. In making his own of Bonnard’s composition however, Collins typically reduced the palette, so that the nude is scarcely distinguished from the surrounding bath, the shape of which enables his penchant for a soft ‘frame within a frame’. The pose of the figure is given more energy in Collins' version, more upright, than Bonnard’s supine image. 'The Bath', was one of the first paintings Collins executed after his arrival in France, from where he continued to send pictures for exhibition to the Richie Hendriks Gallery, Dublin. It was purchased by the singer Luke Kelly of the Dubliners, and acquired from his partner Madeleine Seiler after the singer’s death in 1984.Collins was one of the first artists to be given a solo exhibition at Dublin’s Hendriks Gallery. It was he who introduced fellow painter Barrie Cooke to the gallery where both men regularly exhibited throughout the 1960s and ‘70s. Despite an irregular output, perhaps related to his bohemian lifestyle, Collins continued to be highly regarded. He was selected to represent Ireland at the Guggenheim Awards in 1958. He was elected honorary RHA in 1982 and became Saoi of Aosdana in 1987.'Patrick Collins, Through Sligo Eyes', formed part of the RTE Art Lives series, screened March 10, 2009.Catherine Marshall, April 2017(1) Fallon, Brian Fallon, 'Patrick Collins; A Modern Celt', Irish Arts Review, Spring, 2009.

Patrick Collins HRHA (1911-1994)Sea Road, MonkstownOil on board, 30 x 37cm (12 x 14½)With Hendriks label versoProvenance: From the collection of Harold Pickering and thence by descent to the current owner.A Chemical Engineer, Harold Pickering was a Director of Calor Gas and made frequent business trips to Dublin in the 1960s. He regularly attended exhibitions at the Richie Hendriks Gallery and collected Irish art by such artists as Gerard Dillon, Arthur Armstrong and Eric Patton. He lent pictures to a group exhibition, Eight Irish Artists, organized by David Hendriks to the Savage Gallery, London, 1962 which included works by Collins. He retired from Calor Gas in 1969. He commissioned Gerard Dillon to do some murals on the walls of his family home Dane House, in Surrey which have unfortunately been painted over in the last decade.

Louis le Brocquy HRHA (1916-2012)Lucan Hand coloured lithograph, 12 x 22cm (4¾ x 8½'')Signed and dated (19)'49Provenance: With the Dawson Gallery (label verso), where purchased by art critic Bruce Arnold; From the collection of the late Gillian Bowler.An example of this lithograph was first exhibited 'Louis le Brocquy Exhibition', Victor Waddington Gallery, Dublin, December 1951, Catalogue No.40.

Albert Irvin RA (1922-2015)Glenmore (1985)Acrylic on canvas, 153 X 213 cm (60 X 84”)Signed and dated (19)’85 versoProvenance: From the collection of the late Gillian Bowler.Exhibited : “Albert Irvin Exhibition: Paintings and prints 1980 - 1995”, RHA Gallagher Gallery, Dublin Nov/Dec 1995, Catalogue No. 7.Literature: Albert Irvin Exhibition catalogue 1995, full page illustration p.27.Albert Irvin grew up in London until he was evacuated to Northhampton following the outbreak of World War II in 1939. He won a scholarship to Northampton School of Art in 1940, but his only formal education as an artist was disrupted by conscription a year later. He became a navigator for the RAF and flew on bombing missions into Germany as a member of 236 Squadron. He returned to London after the War and immediately began a precarious career, supported in this by his artist wife, Betty, whom he had met as a student and by working as a screen printer on Laura Ashley’s first fabric designs. Associated with the Saint Ives’ painters Terry Frost and Peter Lanyon in the 1950s and 60s, his career as a painter began to come together after he had been exposed to shows of American Abstract Expressionism in the 1960s, when he also began to teach part-time in Goldsmith’s College, London. His large scale, flamboyant paintings became popular only in the 1980s and 90s, when he was in his sixties, and when he was a prominent figure in reviving British Painting. Bert, as he was known to his many friends, was recognized in Ireland from the early 1980s when he was included in ROSC 1984 and given a solo exhibition at the Butler Gallery a year later.Irvin’s abstract paintings are thoroughly informed by his urban background, although his vision must also have been influenced by seeing the cities of Germany from the air and through the prism of navigational maps. As he put it, ’The traversing of the canvas with a loaded brush stands in direct relation to the traversing of the spaces in which I live and have my being’. Even their titles bear witness to this. From ‘Soho’ (IMMA, Collection), to ‘Battersea’, ‘Piccadilly’, and ‘Clapham’, they spell out a sense of the energy and bustle he found as he travelled between his home and his studio. The architectural nature of cities explains the importance of the rectangle and the square for him, as he points out they echo the ‘given of his world’. Oval canvases attracted him but he found that they dominated the painting. The more static rectangle gave him the scope to play off the energy in the painting against its outer edge, and that energy is the subject of his work.‘Glenmore’ is a little different. The title and date suggests that it was prompted by his visit to Kilkenny and rural Ireland in 1985, although painted in his London studio. “I don’t make use of direct appearances so there is no way in which I’ll produce holiday snaps”, (1) he told Peter Hill, so ‘Glenmore’ offers nothing superficially descriptive of the place it references in the title, it remind us, instead, of Irvin’s love of music and his belief that art is most effective when communicating through a language of abstract form and rhythms. Thus the open composition employed in ‘Glenmore’, the more expansive areas of yellow, when compared to his busier, urban paintings, suggest a relaxed lyricism. The spatial relationships and softer open curvilinear marks here speak of ease and pleasure. Irvin continued to visit Ireland on numerous occasions with Betty, was given a retrospective exhibition at the RHA in 1995, to which this painting was lent, and even curated an exhibition at IMMA in 1991, dedicated to his friend, the Irish artist, Tim Mara. He died at the age of 92 in 2015, painting right up to his death. He is survived by his wife Betty and their daughters.Catherine Marshall, April 2017(1) Albert Irvin, interviewed by Peter Hill, in 'Albert Irvin', Butler Gallery, Kilkenny, 1985.

Albert Irvin RA (1922-2015)Tanza (1986)Acrylic on canvas, 152.5 X 183 cm (60 X 72”) Signed and dated (19)’86 versoProvenance: From the collection of the late Gillian Bowler.Exhibited: Albert Irvin Exhibition”, The Hendriks Gallery, Dublin 1986, where purchased by Gillian Bowler.‘Tanza’ (1986), more compact and tighter in its organization than ‘Glenmore’, is also expressive of Albert Irvin’s belief in the power of abstract shapes to convey feeling more intensively than representation. Music, which he saw as the embodiment of this quality was deeply important to him and his taste embraced classical musicians like Rostropovich, but also experimental composers like Morton Feldman. Through his abstract painting he strove for the immediacy of communication with the spectator that music invariably provides. Like Kandinsky, he believed that both art forms employ a language ‘about the world’ rather than ‘of’ it.The basic structural elements in ‘Tanza’ come from a well-tried and tested group, - a strong diagonal, used alone or in slightly varying parallel groupings, often bridged or intersected by a more horizontal one. These are generally accompanied by a range of minor motifs, such as chevrons, quatrefoils, flower head or star-like shapes and circles. Flat areas of colour are interrupted and articulated by splashes and droplets of colour deposited by a flick of a loaded brush or sprayed out from a squeegee. Irvin often arranges torn and cut-out coloured paper onto sections of the canvas to try out colour arrangements and these add a sense of layering, of past and present, before and after to the paintings, along with the idea of constant movement, to and fro, traverses and reverses. The origins of his marks and motifs tell an interesting story too. One of the most powerful influences on Albert Irvin’s work is a celebrated war painting, ‘Battle of Britain’, 1941 (Imperial War Museum, London) by Paul Nash in which the frenzy of the battle is revealed only in the tangle of smoke trails left in the sky by the fighter planes. Irvin points to this abstract tangle as the most powerful evidence of what has gone on during the engagement, and used similar methods to trace physical journeys, their speed, direction, strength and so on in his own work. Similarly, the abstract language of Australian Aboriginal art to record their history offered him a model for his own formal development, but he is careful not to borrow from other artists or cultures unless he has shared their cultural experience. On a visit to Venice in the 1990s he saw carved quatrefoils on the Doge’s Palace and used them widely in his later paintings.Albert Irvin was a tall man and he tended to paint on a grand scale which, combined with his zest for colour, makes his work particularly popular for hospitals, universities and other public buildings around the world. But he was also an expert print-maker, working just as comfortably in that medium, with considerably smaller compositions. Catherine Marshall April 2017

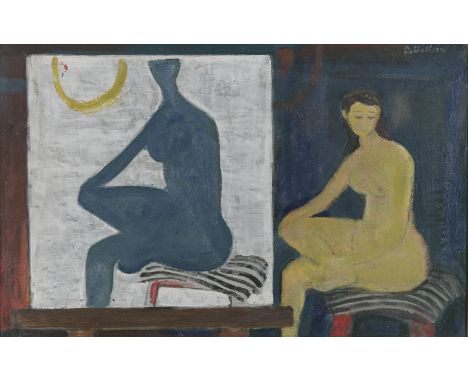

Gerard Dillon (1916-1971)Model and canvasOil on board, 34.5 x 54.5cm (13½ x 21½'')SignedExhibited: RHA Annual Exhibition 1965, Catalogue No. 136'Gerard Dillon Exhibition', Tulfarris Art Galley, June 1980, Catalogue No.16, where purchased.Provenance: From the collection of the late Cyril Murray, a friend of the artist from the 1940s.This work which was exhibited at the RHA is part of a series the artist exhibited at the Dawson Gallery in April, 1965 entitled, ‘Canvases and Clowns.’

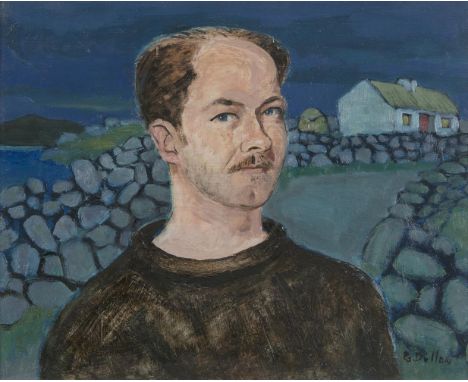

Gerard Dillon (1916-1971)Self in InishlackenOil on board, 31 x 37.5cm (12 x 14¼'')Signed; inscribed with title versoExhibited: ‘Gerard Dillon, Early paintings of The West’. The Dawson Gallery, 4-27 March, 1971 Cat No.27; 'Gerard Dillon Exhibition', Tulfarris Art Gallery, July 1980, Cat No. 22 where purchasedProvenance: From the collection of the late Cyril Murray, a friend of the artist from the 1940s.Influenced by Van Gogh, Dillon enjoyed painting self-portraits in various mediums throughout his career. In the 1950s, his comic spirit endowed him to introduce quirky stand-ins alluding to his presence, records scattered on a floor, legs sticking out from the foreground, shoes tucked under a stool or socks dangling from a fireplace. Referring to these self-portraits, George Campbell remarked in 1974 in a tribute radio programme, ‘practically everything he painted was a self- portrait-himself dickeyed up in some costume or another.’ This work, ‘Self in Inishlacken’ relates to the year he lived with his cat, ‘Suzy Blue Hole’ on Inishlacken Island, a remote picturesque island off the coast of Roundstone in 1951. Encouraged by Victor Waddington to spend more time in Connemara, Dillon bartered a cottage in exchange for a painting which came with two currachs. This work is not typical of Dillon’s style from this period which suggests it was executed after 1951.In semi-darkness, Dillon is depicted half-length wearing a brown jumper gazing directly at the viewer. Standing confidently, stone walls, a cottage and haystack appear on the right and on the left, the sea and mainland. Dillon’s lips are not smiling but his sideward glance regards us with smirking interest. In late 1950, critics labelled Dillon’s views of Connemara at his first solo show at Victor Waddington’s gallery as ‘Stage Irish.’ In 1951, in the Envoy, Dillon defended himself in ‘The Artists Speaks’, ‘I suppose these same critics call Synge’s “Stage Irish”, and deny that his work is art…’ Interviewed years later on his views of critics, Dillon responded, ‘I’m too conceited to worry what a non-painter say’ but conceded, ‘we are all children not just artists. We all like being patted on the head, for what we are or what we do.’ (Marion Fitzgerald ‘The Artist Talks,’ Irish Times, 23/9/64 p.11)In 1994, James MacIntyre wrote ‘Three Men on an Island’ an account of how he adapted to life on the Island in 1951 with Dillon and George Campbell. MacIntyre was prompted to go to the Island after receiving a letter from Dillon inviting him to join him. ‘You’ll love it. Stone walls, thatched cottages, a real peasant life, just up your street. You’ll need £15 for expenses, there’s no rent as I have it for the year. Try and get over next month. Drop me a line when you are coming. Yours Gerard’. Over several months, family and friends visited the Island including Drogheda artist, Nano Reid. The two friends would regularly row over to the mainland to be entertained by the writer Kate O’Brien. Learning of Dillon’s death in June, 1971, Kate O’Brien recalled memories of Dillon’s time on Inishlacken in her column, ‘Arts & Studies, Long Distance’ in the Irish Times, ‘I remember one time he [Gerard] and Nano were inhabiting some old huts over on Inishlacken, a desolate island…I was walking down by the Monastery, and I saw out on the quite rough water Nano and Gerard rowing like mad in a little bit of a currach. They were rowing for home, and I watched them, with anxiety. Because clearly neither was any kind of an oarsman, the tide was running against them, and clearly, they were rowing contrarywise to each other…I have seldom seen anything funnier.’ In the last paragraph, she added ‘He [Gerard] was very gentle, very kind; and was without pretension-indeed, he did not understand what pretension was. But he will be remembered…we can be sure in his dear Belfast, and in such a quiet place as Roundstone.’ Popular among his friends, Dillon’s self-portraits charter his development as an artist and reveal his impish humour.Karen ReihillApril, 2017

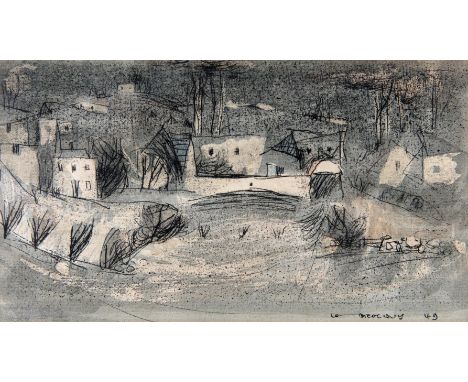

Gerard Dillon (1916-1971)PossessionsMixed media, 56 x 76cm (22 x 30'')SignedExhibited: 'Gerard Dillon Exhibition', The Mercury Gallery, London, April 1967, Catalogue No.33'Gerard Dillon Exhibition', Tulfarris Art Galley, June 1980, Catalogue No.14, where purchased.Provenance: From the estate of Leo Smith, Beverly Smith storage label numbered 149; afterwards in the collection of Cyril Murray, a friend of the artist from the 1940s.

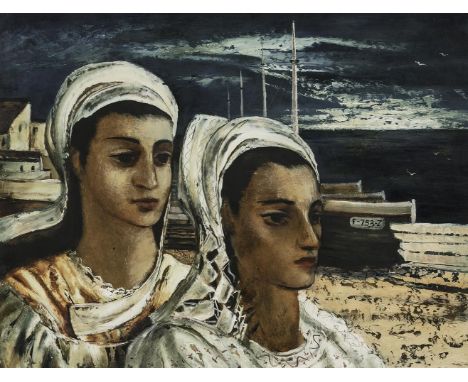

Daniel O'Neill (1920-1974)Fishermen's WivesOil on board, 51 x 67cm (20 x 26¼'')SignedProvenance: The collection of the late Sheila Tinney.Exhibited: RHA Annual Exhbition, 1950, Catalogue No.172; Daniel O’Neill Paintings 1945-51, Victor Waddington Galleries, Dublin, Cat No.10Born in Belfast, O’Neill’s painting career coincided with the outbreak of the second world war. His romantic depictions of human emotion, birth, love, death and suffering had instant appeal at his first solo show at Victor Waddington Galleries in October, 1946. Under contract with the dealer until the late 1960’s, Victor Waddington chose O’Neill’s pictures for touring exhibitions in New York, Amsterdam and London while at home, he selected his paintings for annual shows and chose this work to represent the painter at the Royal Hibernian Academy in 1950. In 1948, O’Neill spent several months in Paris. Titles in exhibition catalogues, ‘Village in Normandy’, ‘Breton Girl,’ and ‘Condé’ in September, 1949 and May 1951 tell us the artist went on sketching holidays in coastal towns in the north west. On his return to Conlig, Co. Down, O’Neill translated sketches into oil paintings for these exhibitions and was known to model his wife, Eileen who had dark eyes and black hair for a number of these paintings. Works from this period are characterized by O’Neill’s fascination with painting techniques and show the influence of artists Utrillo, Van Gogh, Rouault and Vlaminck.As dusk falls, two fishermen’s wives stand together waiting for the return of their husband’s boats in a coastal fishing village. The appearance of a registration number with the letter ‘F’ on the side of a boat probably represents the chief fishing port of Fécamp in Normandy, in the northeast of Le Harve located a few hours from Paris. O’Neill accomplishes surface quality as well as a pervading sense of foreboding in the composition. In the foreground, impasto has been applied to the headdress with a palette knife and the robe has been embellished with decoration by using the end of a brush. Dabbing a sponge on the beach area and squeezing liquid paint from a pinhole in the artist’s tube has resulted in a lace like effect on the neckline of the taller figure. The row of boats and absence of activity indicate fisher folk have returned home after a day out at sea. The calmness of the scene is disrupted by the darkening sky and uneasy expressions of the women. As light fades, sea birds leave but the fishermen’s wives remain standing one behind the other in a supportive role as they stare blankly out into the dark empty sea. O’Neill’s exhibition at Waddington’s in 1951 received several favorable reviews. One art critic commented, ‘his men and women have an innocent, far-away gaze, and they wear their scant garments with elegance…’ and further praised the technique of this work ‘…modelling with the brush the deep pools of brown which give the eyes of his ‘Fishermen Wives’ such daring candor…most of all he excels at making lonely skies of deep blue which create the atmosphere he requires to bewitch us into believing in the absurdly mystical world of fancy. The fact remains that he makes us believe.’ (Irish Press, 21 May, 1951, pg.3)Karen ReihillApril, 2017

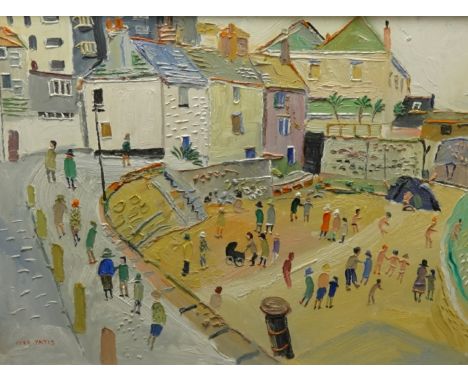

Fred Yates (1922-2008), signed oil on canvas, 'St Ives', 75cm x 100cm, with overpainted white frame. Provenance from the seller 'Fred Yates was my art teacher at Teignmouth Secondary School. Fred would ask me to undertake various building tasks at his houses in Penzance and Lostwithiel, with the money that he paid me I purchased his art work. The picture frame on the was painted by him. He suggested that I buy the monochrome version of the same scene, as it would blend with any décor, when my wife and I invited him one afternoon for tea at our home, Fred used to say that he loved the ritual of afternoon tea'

-

635938 Los(e)/Seite