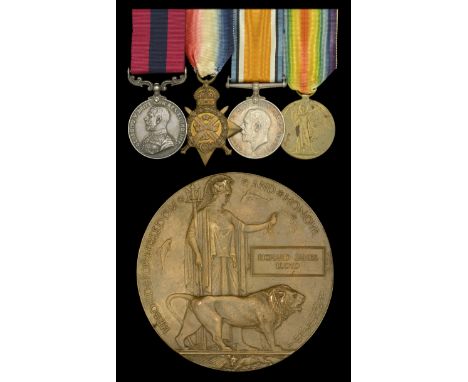

A Great War D.S.O. group of three awarded to Lieutenant J. Martin, Royal Naval Reserve and Mercantile Marine, who was decorated and commissioned for his zeal and devotion to duty on the occasion that the lightly armed merchantman Caspian was attacked and sunk by the German submarine U-34 in May 1917; the Captain having being killed, he took charge, only abandoning the ship after 23 of her crew were dead and all ammunition was spent - he later commanded the Q-ships Dargle and Fresh Hope 1917-18 Distinguished Service Order, G.V.R., silver-gilt and enamel, with integral top riband bar; British War and Victory Medals (Lieut. J. Martin, R.N.R.) good very fine (3) £1,000-£1,400 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- D.S.O. London Gazette 19 December 1917: ‘In recognition of zeal and devotion to duty shown in carrying on the trade of the country during the War.’ James Martin, a native of Sunderland, was born in 1847 and was granted a temporary commission as a Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve on 10 August 1915, aged 68. He was given command of the Admiralty trawler Filey from 30 August, armed with one 12 pounder gun. The following year he was discharged from the Royal Naval Reserve and had his commission cancelled due to misconduct in being drunk on board his ship on 20 January 1916. However, finding employment as Chief Officer of the lightly armed merchantman S.S. Caspian of the Mercantile Marine, Martin was to be redeemed by his actions the following year when on 20 May 1917, the highly successful German submarine U-34 attacked the S.S. Caspian 3.5 miles off Alicante. During an action lasting over two hours, in which the Master, Arthur Douse, and 23 members of the crew were killed, Martin was left in charge of the Caspian and only after all the ammunition was used, the surviving crew members took to the boats. The U-boat then took just three prisoners aboard (the Chief Engineer, 2nd Officer and a gunner) and then proceeded to torpedo and sink the Caspian. Chief Officer Martin was awarded the D.S.O. for his zeal and devotion to duty on this occasion and gazetted a Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve once more, later receiving his award at the hands of the King at Buckingham Palace on 11 September 1918. He was 70 years old at the time of the action and was stated at the time to be the oldest man ever to have won the decoration. Three other crew members received the D.S.C. Martin’s re-appointment as Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve was dated 19 May 1917 and he was given command of the Q-ship Dargle in the following month, a topsail schooner fitted out with a 4-inch and two 12-pounders. Operating out of Lerwick, she certainly had a number of encounters with enemy submarines. In a lengthy patrol report sent to the Admiral Commanding, Orkney and Shetland, on 16 August 1917, Martin expressed his doubts about the Dargle’s suitability for Q-ship operations: ‘It is my opinion that this vessel owing to her uncommon build is marked and suspected by enemy submarines of being armed. Three times in my experience submarines have been in the vicinity and no attempt made to attack us has been made until we had a torpedo fired at us. As a decoy ship she is a failure, and I should recommend her being handed back to her owners, and the guns, engines and material being taken out of her and fitted in a vessel more serviceable.’ Martin’s report swiftly invoked the Admiral Commanding to send a scathing report to the C.-in-C. Grand Fleet: ‘I consider that the present Commanding Officer of the Special Service Vessel Dargle is not suitable for appointment in command of a Special Service Vessel. Lieutenant J. Martin, R.N.R., is of an excitable temperament which is most undesirable. At various interviews he has not impressed me or members of my staff as being a suitable officer for his present command. He is constantly using his motors and does not appear to realise the importance of making his vessel look like a peaceful merchant ship, as will be seen from the letter of the Rear-Admiral, Stornaway ... I am therefore desirous of giving her another trial under a new Commanding Officer and submit that Lieutenant Martin may be relieved.’ As a result, according to Carson Ritchie’s Q-Ships: ‘Martin resigned from his command on the grounds of ill-health, but Captain James Startin, Senior Naval Officer, Granton, who felt that he was a very capable officer, but ‘certainly difficult as regards naval etiquette and discipline’, had him transferred to another vessel. A year later, as commander of the Fresh Hope, another sailing Q-ship, Martin justified this good opinion by bringing the fore-and-aft schooner into an encounter with a U-boat on which he scored four direct hits.’ Lieutenant Martin was placed on the retired list on 28 June 1920 and died in 1929 aged 82. Sold with copied research and medal roll extracts, that shows that the recipient additionally received the 1914-15 Star. Another Lieutenant J. Martin (John Martin) is also on the medal roll of the Royal Naval Reserve, also entitled to a 1914-15 Star, British War Medal, and Victory Medal.

We found 16046 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 16046 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

16046 item(s)/page

A Great War ‘Western Front’ D.C.M. group of four awarded to Corporal R. J. Lloyd, Shropshire Light Infantry, who was killed in action on 18 April 1917 Distinguished Conduct Medal, G.V.R. (9718 Cpl. R. J. Lloyd. 1/Shrops: L.I.); 1914 Star (9718 Pte. R. J. Lloyd. 1/Shrops: L.I.); British War and Victory Medals (9718 Cpl. R. J. Lloyd. Shrops. L.I.); Memorial Plaque (Richard James Lloyd) slight edge dig to first, otherwise very fine (5) £900-£1,200 --- D.C.M. London Gazette 14 November 1916. ‘For conspicuous gallantry and presence of mind. When distributing bombs prior to attack a fuzed bomb without a safety pin commenced to burn, and the man holding the bomb dropped it. Cpl. Lloyd, grasping the situation, ordered the men under cover, picked up the bomb, and threw it away. It exploded almost as it left his hand. His prompt courage undoubtedly saved many lives.’ Richard James Lloyd, from Dolgelley, Merioneth, living in Betton Strange, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, attested into the Shropshire Light Infantry and served during the Great War with the 1st Battalion on the Western Front from 10 September 1914. Advanced Lance Sergeant, he was killed in action on 18 April 1917 and is commemorated on the Loos Memorial, France. Sold with copied Medal Index Card and copied research.

Three: Able Seaman A. Harris, Royal Navy, who was killed in action when H.M.S. Daring was torpedoed by the German submarine U-23, under the command of the ‘Wolf of the Atlantic’ Otto Ktretschmer, and sank off Duncansby Head, 18 February 1940 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; War Medal 1939-45, with named Admiralty enclosure, in card box of issue, addressed to ‘Mr. J. T. Harris, 6 Collington Lane, Bexhill-on-Sea, Sussex’, nearly extremely fine (3) £120-£160 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Albert Harris served during the Second World War as an Able Seaman in the D-class destroyer H.M.S. Daring, that had, for a time, been the first command of Lord Louis Mountbatten. On 18 February 1940 H.M.S. Daring was one of four destroyers escorting a convoy from the Norway campaign to the U.K. In the early hours of the morning the convoy was sighted by U-23, commanded by the man who would later become known as the ‘Wolf of the Atlantic’, Otto Ktretschmer. At a point some 30 miles East from Duncansby Head U-23 found herself trapped on the surface between the two port-side escorts of the convoy. In order to enable an escape Kretschmer decided to attack the stern destroyer, H.M.S. Daring. Two torpedoes were fired and Daring was hit; almost immediately later a secondary explosion ripped through the ship, broke her in half she sank within two minutes, with the loss of 157 Officers and crew. There were only 5 survivors. Harris was amongst those killed. He is commemorated on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial. His medals were sent to his father Mr. J. T. Harris. Sold with a photographic image of the ship’s crew.

A Great War ‘Battle of Passchendaele’ M.M. group of nine awarded to Sergeant J. J. Cronje, 4th Regiment, South African Infantry, later South African Medical Corps, who was decorated for repeatedly hauling wounded men on his back and carrying them from the Menin Road to the comparative safety of Allied First Aid Posts and Casualty Clearing Stations Military Medal, G.V.R. (2290 Pte. J. J. Cronje. 4/S.A. Inf:); 1914-15 Star (Pte. J. J. Cronje 6th Infantry); British War and Bilingual Victory Medals (Pte. J. J. Cronje. 4th S.A.I.); 1939-45 Star (228144 J. J. Cronje) this privately engraved; Italy Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; Africa Service Medal, the last four officially impressed ‘228144 J. J. Cronje’, mounted as worn, suspension slack on BWM, nearly very fine and better (9) £360-£440 --- M.M. London Gazette 14 January 1918. The original recommendation - initially for a D.C.M. - states: ‘This man who was a Company stretcher bearer showed great gallantry and devotion to duty during the operations at Ypres on 20 September 1917. Whilst acting as one of a party of stretcher bearers, he continued to carry wounded men to safety on his back under heavy shell fire, after the remaining members of the party were either killed or wounded.’ John Cronje, a blacksmith, was born in Riversdale, South Africa, on 9 September 1894, and attested for the 1st South African Infantry on 14 August 1915. Posted to the Western Front with “K” Company, 4th S.A.I., his papers record that he was wounded in action on 28 February 1917, 18 April 1917 and 24 March 1918; the latter occasion is stated as a severe injury to the shoulder and left knee, received in the opening days of the German Spring Offensive - possibly at Marrieres Wood. Invalided to England 30 March 1918, Cronje embarked home to South Africa per Cawdor Castle and was demobilised at Maitland 24 May 1919. He later returned to service at Kimberley with the South African Medical Corps from 24 December 1941. Appointed Corporal in June 1942 and Sergeant in October 1944, he witnessed extensive service as a male nurse in Italy and North West Europe; he was demobilised in March 1946, his character rated as ‘exemplary’. Sold with copied service records for both campaigns; with private research detailing the names of 4 comrades recommended for the M.M. alongside Cronje, all members of “D” Company, 4th S.A.I.

A scarce M.S.M. for gallantry awarded to Acting Company Sergeant Major J. S. Holborn, M.M., 4th Regiment, South African Infantry, who was twice decorated for initiative and courage and was later killed in action during the German Spring Offensive on 17 April 1918 Army Meritorious Service Medal, G.V.R., 1st issue (X15 A.Cpl. J. S. Holborn. 4/S.A. Inf:) traces of adhesive to reverse, minor edge bruise, nearly extremely fine and scarce to unit £300-£400 --- M.M. London Gazette 9 July 1917. The original recommendation - initially for a D.C.M. - states: ‘In the operations on 9 April [1917] this Non Commissioned Officer was in charge of a platoon and displayed great initiative and courage. In the attack on the second objective he led a bombing attack against a portion of the enemy and dispersed them. In the operations of 12 April, he again led his platoon in a very gallant manner and by his courage act - a very splendid example to the men. In this attack he was wounded, but in the arm and the leg but refused to leave his post for nearly four hours after being wounded and until he had been assured that his platoon was in a secure position.’ M.S.M. London Gazette 9 March 1917. The original recommendation states: ‘For Gallantry in the Performance of Military Duty. During a course of instruction in live grenade throwing, an N.C.O. threw a live mills bomb which lodged in the parapet of the trench just above his head. L/Cpl. Holborn pushed the man aside and grasping the bomb threw it over the parapet, thus averting a most serious accident and probably saving several lives. Deed performed at Bordon, 23 July 1916.’ John Simpson Holborn, a boilermaker, was born in Gourock, Scotland, around 1876, and attested for the 4th South African Infantry at Bordon on 29 November 1915. Allocated the Regimental number ‘X15’ and attached to “K” Company, he disembarked at Rouen for the Western Front shortly after his M.S.M. winning exploits and was promoted Corporal in the trenches on 8 August 1916. Further promoted Sergeant 6 November 1916, his service records state that he survived the Battle of the Somme but was wounded in action on 12 April 1917, during the action for which he was awarded the Military Medal. Evacuated to Eastbourne suffering from a severe gunshot wound to the right hip, he returned to Belgium in March 1918 as Acting Company Sergeant Major. He was killed in action a short while later on 17 April 1918; he has no known grave and is commemorated upon the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial, Belgium. Sold with copied service record and private research.

The 3-clasp Naval General Service medal awarded to John D. Lambeth for his services as Landsman on board the Namur on 4 November 1805, as Ordinary Seaman on board the Valiant at Basque Roads, and as Able Seaman in the boats of the same ship at the capture of two French brigs in September 1810 Naval General Service 1793-1840, 3 clasps, 4 Novr. 1805, Basque Roads 1809, 27 Sep Boat Service 1810 (Jno. D. Lambeth) the last four letters of surname corrected from ‘Lambert’, edge bruise and scratch to obverse, otherwise very fine £5,000-£7,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- 33 clasps issued for the Boat Service action on 27 September 1810. ‘On the night of September 27th, the boats of the Caledonia, one hundred-and-twenty, Captain Sir H. Neale, Valiant, seventy-four, Captain R. Oliver; and Armide, thirty-eight, Captain R. Dunn, lying in Basque Roads, were despatched under the orders of First Lieutenant Hamilton of the Caledonia, to take or destroy three brigs laden with Government stores, anchored under the protection of a strong battery at Pointe du Ché. As it was known that the enemy had strengthened the position with field pieces, and that a strong body of troops was assembled for the protection of the vessels, a party of one hundred and thirty marines, commanded by Captains T. Sherman and McLachlan, with Lieutenant Little, was added to the seamen from the three ships. At half-past two the marines were landed under Pointe du Ché, but the alarm was given by the brigs, and under a smart fire Lieutenant Little advanced, captured the battery and spiked the guns. In the meantime Captain Sherman took position on the main road, facing the village of Angoulin, supported by one of the launches with an eighteen-pounder carronade. The enemy advanced from the village and attacked him, but were driven back with loss. The French then made another attempt with a field piece, but were charged with the bayonet, put to flight, and the gun taken. While this was going on, the seamen had captured two of the brigs, and destroyed the other, and the party re-embarked without losing a man. Lieutenant Little and one man were wounded. The enemy left fourteen dead in the battery, but what loss they sustained from the fire of Captain Sherman's division and the launch could not be ascertained.’ (Medals of the British Navy by W. H. Long refers). John Lambeth/Lambert is confirmed on the rolls as Landsman aboard Namur at Strachan’s action on 4 November 1805, as Ordinary Seaman aboard the Valiant at Basque Roads, and as Able Seaman in the boats of the same ship the capture of two French brigs off Point du Ché, in the Basque Roads, by boats from Armide, Caledonia and Valiant. He is shown as Lambeth on all ship’s books but incorrectly as Lambert on the clasp application list for 4 November 1805, and as Lambeth on the clasp application lists for the two latter clasps. He consequently has two entries in the Colin Message roll who describes him as a ‘man of mystery’. Sold with copied muster lists and some professional research.

‘For most conspicuous gallantry. Lieutenant Dean handled his boat [M.L. 282] in a most magnificent and heroic manner when embarking the officers and men from the blockships at Zeebrugge. He followed the blockships in and closed Intrepid and Iphigenia under a constant and deadly fire from machine-guns at point blank range, embarking over one hundred officers and men. This completed, he was proceeding out of the canal, when he heard that an officer was in the water. He returned, rescued him, and then proceeded, handling his boat throughout as calmly as if engaged in a practice manoeuvre. Three men were shot down at his side whilst he conned his ship. On clearing the entrance to the canal the steering gear broke down. He manoeuvred his boat by the engines, and avoided complete destruction by steering so close in under the Mole that the guns in the batteries could not depress sufficiently to fire on to the boat. The whole of this operation was carried out under a constant machine-gun fire at a few yards range. It was solely due to this officer’s courage and daring that M.L. 282 succeeded in saving so many valuable lives.’ The citation for the award of Percy Dean’s V.C., refers. The outstanding and important Great War C.G.M. group of four awarded to Chief Motor Mechanic S. H. Fox, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, who was decorated for his gallantry in Percy Dean V.C.’s M.L. 282 in the famous St. George’s Day raid on Zeebrugge in 1918 Conspicuous Gallantry Medal, G.V.R. (M.B.1872. S. H. Fox. Ch. M.M., R.N.V.R. Zeebrugge-Ostend 22-3. Apl. 1918.); British War and Victory Medals (M.B.1872. S. H. Fox. C.M.M. R.N.V.R.); France, 3rd Empire, Croix de Guere 1914 1917, with bronze palm, mounted court-style for wear, nearly extremely fine (4) £10,000-£14,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Spink, June 1984 and March 1997. C.G.M. London Gazette 23 July 1918: ‘The following awards have also been approved.’ The original (joint) recommendation states: ‘The three ratings above mentioned were amongst those who volunteered to man Motor Launches detailed to rescue the crews of the blockships, and it was largely due to the coolness and courage with which the crews of these Motor Launches carried out their duties that so many officers and men were rescued. These three men displayed most conspicuous gallantry in the face of intense gun and machine-gun fire at short range.’ French Croix de Guerre: issued by authority of the Marine Nationale, Paris, 28 August 1918: ‘He volunteered to go out in a motor boat to pick up the crew of blockships under intense artillery and machine gun fire.’ Sydney Harold Fox was born at Wellington, New Zealand, on 19 June 1892, and joined the Royal Navy at that location as a Motor Mechanic in October 1916. He subsequently served in Motor Launches (M.L.s) of Attentive III from March 1917, was promoted to Chief Motor Mechanic on 1 July 1917, and continued in that role until March 1918, when he volunteered for the Zeebrugge raid as a Chief Motor Mechanic in M.L. 282. The extraordinary exploits of M.L. 282 in the epic St. George’s Day raid on Zeebrugge in April 1918 resulted in the award of the aforementioned V.C. to 41-year-old Percy Dean, in addition to Fox’s C.G.M., a D.S.M. to fellow Motor Mechanic Edward Whitmarsh and a D.S.C. to Lieutenant Keith Wright. In his post-raid report, Dean made special mention of the ‘excellent work’ done by these men The two-mile retreat from Zeebrugge, in full view of the enemy batteries on the Mole and elsewhere, probably created the greatest challenge of all. But Dean courageously responded by taking M.L. 282 right alongside the Mole wall, thus preventing the enemy gunners from being able to depress their guns low enough to engage him. Nonetheless, with his vessel crowded with over 100 men, many of them wounded or dying, it was an extraordinary feat to clear the harbour and gain the open sea, especially when the rudder was made redundant and it became necessary to steer directly by the engines - no doubt an episode in which Chief Motor Mechanic Fox proved to be a tower of strength: it was later discovered that the rudder’s steering lines had been obstructed by a corpse. Ultimately M.L. 282 was met by Admiral Keyes’s flagship, H.M.S. Warwick, and all her ‘passengers’ safely embarked. Keyes was greatly impressed by what he saw, afterwards recording in his despatch that he was ‘much struck with the gallant bearing of Lieutenant Dean and the survivors of his crew. They were all volunteers, and nearly all had been wounded and several killed.’ Indeed, only four members of this gallant M.L.’s company came through unscathed, testament indeed to the ferocity of the enemy’s fire and the highest gallantry of Fox and his shipmates. Fox subsequently served in M.L.’s in the Mediterranean from depot ship H.M.S. Caesar until posted to the British Caspian Flotilla to man C.M.B.’s in 1919, then to H.M.S. Julius at Constantinople, returning to the United Kingdom in March 1920 where he was discharged from the Navy on 20 June 1920, one of the last New Zealanders to be demobilised from the First World War. ’Amongst the New Zealanders who participated in the recent naval action at Zeebrugge was Mr. Sydney Fox, son of Mr. Louis H. Fox, house steward at the Wellington Hospital. Writing to his parents, Mr. Fox, who left New Zealand as a member of the first Motor Boat Patrol, gives some particulars of the fight. “We went up into the canal,” he writes, “to rescue the crews of two ships that we sank there. Well, there were only four of us on our ship who came out alive, and I was one of them. It was a very desperate job. The writer refers to one of his pals, Mr. Jack Batey, who was killed in the engagement. Mr. Batey, who formerly lived at New Plymouth, leaves a widow. At latest advice Mr. Fox was chief engineer of the vessel on which he was at the time of the Zeebrugge engagement. (Grey River Argus, 25 June 1918 refers). Sold with a file of research, including a photocopy of the recipient’s Croix de Guerre award certificate.

The Royal Navy L.S. & G.C. medal awarded to William Leonard, Captain of the Forecastle, H.M. Sloop Orestes, in 1836 after 24 years’ service Royal Navy L.S. & G.C., Anchor obverse (Wm. Leonard, Captain of Forecastle, H.M. Sloop Orestes, 24 Years) with old ring and loop/bar wire suspension, contact marks and edge bruising, otherwise very fine £1,200-£1,600 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Cleghorn Collection 1875; Sotheby’s, May 1895; Glendining’s, December 1910; Sotheby’s, July 1979; Dix Noonan Webb, March 2005. William Leonard/Lennard entered the Royal Navy as a Boy 2nd Class in May 1809 via the Marine Society. In his subsequent career of 35 years, he won entitlement to the Naval General Service 1793-1840 with clasps for Java and Navarino, the former for services as a Boy 2nd Class in H.M.S. Bucephalus and the latter as a Captain’s Coxswain in the Cambrian. However, as verified by extensive accompanying research, one of the most dramatic moments of his career occurred on 23 June 1822, when his ship, the Drake, was shipwrecked off Newfoundland with the loss of one third of her crew. In a letter to the Admiralty, a senior surviving crew member, Gunner Thomas Elgar, wrote: ‘At half past seven o’clock the land was observed with heavy breakers ahead - immediately we hauled our wind, but not being enabled to clear the danger on that tack, attempted to stay the vessel, but from the heavy sea her stern took the breakers, and immediately fell broadside on the rocks, where the sea beat completely over her. The masts were cut away with a view to lightening the vessel, as well as affording a bridge to save the crew, but without success in either point. In a few moments she bilged and there did not appear the slightest prospect of saving a man. The cutter was launched over the lee gangway but sunk, immediately a man attempted with the deep sea leadline to swim on shore but the current setting so strong to the N.E. he was almost drowned in the attempt. The only hope remained in the gig (the jolly boat having been washed away) and she was launched from the forecastle [Leonard’s domain] with the Boatswain when fortunately a heavy surf washed her upon a rock not communicating with the Main, and she was dashed to pieces but the Boatswain succeeded in scrambling to the top of the rock with about seven fathoms of line, the rest having been carried away with the wreck of the fore and main masts. The forecastle, hitherto the only sheltered part of the vessel, was now abandoned for the poop, and all hope of saving the vessel being gone it was deemed advisable to quit her. The people severally stepped from the poop upon the rock except for a few who endeavoured to swim on shore - most of whom perished. Captain Baker after seeing the whole crew safe on the rock followed himself, but it was now found that the rock was insulated, and the tide making would cover it. The Boatswain observing this swam with a small line and fortunately reached the Main and coming opposite the rock on which we landed, threw the line across, by which the greater part of the people succeeded in crossing, which would otherwise have been impossible. Captain Baker, not withstanding that he was repeatedly solicited to cross, resolutely refused alleging till every soul was safe he could not think of it. Shortly after, the line, from a heavy sea was washed away, and in consequence of the surf and darkness of the night it was quite impossible to obtain another. Every instant the water continued to rise, when the officers and ship’s company used every endeavour, by tying their handkerchiefs together, to make another holdfast but that proving too weak it was found impracticable, and we were reluctantly compelled to abandon them to their fate. At daylight when we visited the beach there was not the slightest trace of these unfortunate sufferers ...’ Over the coming weeks a good deal of official correspondence regarding the loss of the Drake was exchanged between the survivors and Their Lordships - much of which survives in ADM 1/2789 - and, at length, in November 1822, when everyone had been safely re-assembled back in the U.K., a Court Martial was held at Portsmouth. All the survivors were duly acquitted, and Leonard received from the examining officers ‘great approbation for his zeal and gallantry in saving the lives of his shipmates.’ A few days later, on behalf of the Petty Officers and ratings of the Drake, Leonard wrote a letter to an old Lieutenant of the same ship - ‘in a truly seamanlike style’ - requesting that a memorial be erected to mark the bravery of their late skipper, Captain Charles Baker, R.N., a request that the Lieutenant forwarded for the attention of Their Lordships at the Admiralty, among others. And by the end of the same month, Leonard’s suggestion had found favour, so much so that today the resultant memorial tablet may be seen at St. Anne’s Church in H.M. Dockyard, Portsmouth. Not so graciously received by Their Lordships was a request by some of Drake’s survivors for remuneration for the loss of their clothes, an Admiralty minute of 21 November 1822 bluntly stating, “Refused”. As it transpired, this was not to be the sole occasion on which Leonard experienced the loss of his ship, for, in January 1828, as related in Marshall’s Naval Biography (see entry for Captain Hamilton, pp. 450-2), he was aboard the Cambrian when she collided with the Isis after an action against several privateers ‘within pistol-shot of the fort of Carabusa’. As a result, she ‘fell broadside to on a reef of rocks’ and became a total wreck. Leonard was awarded his L.S. & G.C. Medal in April 1836, his then Captain recommending him as ‘a man the most exemplary in every respect’, and, although “paid-off” in April 1838, he chose - in common with other old seadogs of Petty Officer status - to rejoin several years later, although on this occasion in the rate of Able Seaman. He was finally discharged in January 1855, by which stage he was in his 60s.

The emotive Dunkirk ‘little ships’ D.S.M. awarded to Engineer Fred Barter, H.M. Yacht Ankh, who, under heavy fire, assisted in ferrying 400 troops from the beaches; it is said that he also delivered a no-nonsense broadside of his own, when Lord Gort, V.C., apparently tried to jump the queue to his boat, a broadside of the four-letter variety Distinguished Service Medal, G.VI.R. (F. Barter, Yacht Engn. H.M.Y. Ankh.) impressed naming, contact marks, otherwise nearly very fine £1,000-£1,400 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Jeffrey Hoare Auction, April 2000. D.S.M. London Gazette 16 August 1940: ‘For good services in the withdrawal of Allied Armies from the beaches at Dunkirk.’ Requisitioned by the Admiralty, H.M. yacht Ankh was taken over by Captain J. M. Howson, R.N., as a temporary H.Q., when she arrived off Dunkirk on the morning of 31 May. She was manned by a handful of naval personnel and civilians. Howson had charge of nine yachts, which he divided between the beaches at Bray and La Panne, but owing to their deep draft they were unable to get close inshore, thereby necessitating the use of small launches and rowing boats to collect the awaiting troops from the beaches. One such boat was manned by Fred Barter and Able Seaman W. F. ‘Frank’ Lunn, R.N., a boat with a capacity for eight people but in which they proceeded to embark 20 at a time. During one return trip to the yachts, the boat was capsized by a near miss bomb, leaving the embarked soldiers floundering in water in full kit. Barter and Lunn swam over a mile to the yachts to collect another boat, and, under fire, returned to the beaches. In fact, they continued their gallant work throughout the day, eventually ferrying a total 400 troops to safety. In an article published in The War Graves Photographic Project Newsletter in the Spring of 2017, Barter’s grandson recalled how Fred never really spoke of his experiences off Dunkirk. He also recalled how he came across an amusing anecdote concerning Field Marshal Lord Gort, V.C. Apparently Gort appeared on the beach and tried to jump the queue to Fred’s boat, an endeavour that was smartly curtailed when the latter told him to “**** off!” Barter may have been a modest man, but he did manage to say a few words to The Hampshire Telegraph and Post, when interviewed in March 1941: ‘Barter shared charge of a rowing boat which was sent ashore to pick up soldiers. Normally the boat held only six, but Barter and his companion got in 20, and towed rafts carrying several other soldiers. “We were sunk by enemy action and had to swim for it,” said Barter. “Many of the B.E.F. men returned to the shore, but Lunn and I swam over a mile back to the yacht, took another boat, and carried on with the good work. Eventually we got nearly 400 soldiers safely on to our yacht.” ’ He received his D.S.M. from King George VI at Buckingham Place on 16 July 1940.

The fine and unique 4-clasp Naval General Service medal awarded to Gunner George Shirley, Royal Navy, who served on board the flagships of Sir Hyde Parker on 14 March 1795, of Sir Horatio Nelson at the Nile, and of Lord Keith in Egypt, later promoted to Gunner Naval General Service 1793-1840, 4 clasps, 14 March 1795, Nile, Egypt, Martinique (Goe. Shirley, Master’s Mate.) original ribbon, nearly extremely fine £12,000-£16,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Glendining’s March 1919. This combination of four clasps appears to be unique. George Shirley joined the Courageux in February 1791, aged 20, and transferred as an Able Seaman to St George in February 1793, flagship of Vice Admiral Sir Hyde Parker (Captain Foley) in Hotham’s action on 14 March 1793. He transferred in March 1798 to the Vanguard, flagship of Rear Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson (Captain Berry), under whom he served as Quartermaster’s Mate at the battle of the Nile, during which he would have been stationed at the wheel (Note that his rate was incorrectly copied down by the medal roll compiler who entered Master’s Mate in error, this being senior to his eventual rate of Gunner and therefore that which appears on his medal). In June 1799, Shirley joined Foudroyant, flagship of Admiral Lord Keith (Captain Beaver) and again served as Quartermaster’s Mate during the operations in Egypt in 1801. Shirley’s qualities must have been well respected for him to have been promoted, possibly as reward, to warrant officer status in August 1801, as Gunner, just ten years after joining the Navy. As one of the most trustworthy and reliable man in any ship, Shirley served as Gunner for the next 35 years. He was present on board the Cleopatra in February 1805 when she fell in with and was boarded and taken by the larger French frigate Ville de Milan. The loss to the British amounted to 22 killed and 36 wounded, the remainder becoming prisoner under a French prize crew. However, six days later, Cleopatra and Ville de Milan were sighted by Leander and neither vessel being in a fit state to fight, both surrendered to the British frigate without a shot being fired. George Shirley’s naval career seems to have come to an honourable end with his discharge to shore from Britannia in December 1836, at the age of about 65 years.

The impressive ‘Flag Officer Royal Yachts’ G.C.V.O., Great War C.B. group of thirteen to Admiral Sir Henry Buller, Royal Navy, who commanded H.M.S. Highflyer in her epic engagement with the German cruiser Kaisar Wilhelm der Grosse off Rio de Oro in August 1914, an action extensively portrayed the pages of ‘Deeds That Thrill The Empire’ The Royal Victorian Order, G.C.V.O., Knight Grand Cross set of insignia, comprising sash badge, silver-gilt and enamels and breast star, silver, with gilt and enamel centre, both officially numbered ‘581’ on reverse, in Collingwood, London numbered case of issue; The Most Honourable Order of the Bath, C.B. (Military) Companion’s neck badge, silver-gilt and enamels, in damaged Garrard, London case of issue; 1914-15 Star (Capt. H. T. Buller, M.V.O., R.N.); British War and Victory Medals (Capt. H. T. Buller. R.N.); Defence Medal 1939-45; Jubilee 1935; Coronation 1953; Russia, Empire, Order of St. Anne, Third Class breast badge by Keibel, gold and enamels, two reverse arms chipped, these last seven mounted court-style as worn; Belgium, Order of the Crown, Knight Grand Cross set of insignia, by Wolravens, Brussels, comprising sash badge, silver-gilt and enamels, and breast star, silver with silver-gilt and enamel centre, in case of issue; Roumania, Order of the Star (Military), Second Class set of insignia, by Resch, Bucharest, comprising neck badge, silver-gilt and enamels, and breast star, silver, with silver-gilt and enamel centre, in case of issue, unless otherwise described, good very fine and better (14) £4,000-£5,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Spink, July 2000. G.C.V.O. London Gazette 11 August 1930: For services as Flag Officer Royal Yachts. C.B. London Gazette 1 January 1919: ‘In recognition of services during the War.’ The original recommendation states: ‘Sank Kaiser Wilhelm de Grosse. Extract from letter to Rear-Admiral, Carnarvon: Captain Buller’s action has their Lordship’s complete approval in every respect for the humane and correct manner in which he did his duty.’ Henry Tritton Buller was born in 1873, the son of Admiral Sir Alexander Buller, G.C.B., of Erie Hall, Devon and Belmore House, West Cowes, and entered the Royal Navy as a Cadet in January 1887. Regular seagoing duties aside, his subsequent career appointments also included his services as First Lieutenant of the Royal Yacht Victoria and Albert in 1902-04, for which he was awarded the Russian Order of St. Anne in October 1904 and advanced to Commander, and as Commanding Officer of the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth between January 1908 and June 1911. On the Prince of Wales passing out of the college in 1911, Buller was appointed M.V.O. (London Gazette 12 April 1911, refers) and advanced to Captain. His next appointment was Flag Captain Home Fleets at Portsmouth, 1911-12, whence he was appointed to the command of H.M.S. Highflyer, the training ship for special entry cadets. On the day hostilities broke out in 1914, Buller in Highflyer captured to S.S. Tubantia, carrying German reservists and a gold shipment. Three weeks later, he found the German commerce raider Kaiser Wilhelm Der Grosse, coaling in Spanish territorial waters off the mouth of the Oro River, West Africa. On offering the faster vessel the chance to surrender, Buller received the signal: “Germans never surrender, and you must respect the neutrality of Spain.” But since it was known that the commerce raider had abused Spanish neutrality by using the river mouth as a permanent base for some weeks, Buller gave warning that he would attack in half an hour, allowing time for the colliers to withdraw with such personnel as the German captain felt fit. Deeds That Thrill the Empire takes up the story: ‘As soon as the period of grace had elapsed the Highflyer again inquired if the enemy would surrender, and when the answer came, “We have nothing more to say,” the action opened without further parley. The British cruiser let fly with one of her 6-inch guns at a range of just under 10,000 yards; but the shot fell short. The enemy’s guns were smaller - 4.1-inch - but much more modern, and before our shells began to hit the enemy the German projectiles were falling thickly around and upon the Highflyer. One shell went between a man’s legs and burst just behind him, peppering him with splinters. Another struck the bridge just after the captain had left it to go into the conning-tower, and knocked a searchlight overboard. All this time the Highflyer was steaming in so as to get her guns well within range; and when the 100lb shells began to hit they “kept on target” in a manner that spoke well for the training of our gunners. One shot carried away a 4-inch gun on the after-deck of the enemy. Another burst under the quarter-deck and started a fire; a third - perhaps the decisive shot of the action - struck her amidships on the water-line and tore a great rent in her side. From stem to stern the 6-inch shells tore their destructive way, and it was less than half and hour after the fighting began that the “pride of the Atlantic” began to slacken her fire. The water was pouring into the hole amidships, and she slowly began to heel to port. Three boat loads of men were seen to leave her and make for the shore … The Highflyer immediately signalled that if the enemy wished to abandon ship, they would not be interfered with; and as the guns of the Kaiser Wilhelm had by this time ceased to answer our fire, the Highflyer ceased also, and two boats were sent off with surgeons, sick-berth attendants and medical stores, to do what they could for the enemy’s wounded. The ship herself was battered beyond all hope, and presently heeled over and sank in about fifty feet of water. Although Highflyer had been hit about fifteen times her losses amounted to only one man killed and five slightly wounded. The enemy’s loss is unknown, but it is estimated that at least two hundred were killed or wounded, while nearly four hundred of those who had escaped in the colliers were captured a fortnight later in the Hamburg-America liner Bethania … ’ The same source concludes: ‘It was noteworthy as being the first duel of the naval war and as being the first definite step in the process of “clearing the seas.” It is not often the Admiralty evinces any enthusiasm in the achievements of the Fleet, and the following message despatched to the victorious cruiser is therefore all the more remarkable: “Admiralty to Highflyer – Bravo! You have rendered a service not only to Britain, but to the peaceful commerce of the world. The German officers and crew appear to have carried out their duties with humanity and restraint, and are therefore worthy of all seamanlike consideration.” Buller departed Highflyer in May 1916, when he was appointed Naval Assistant to the Second Sea Lord at the Admiralty, but he returned to sea as Flag Captain in the Barham in April 1918, and as Commanding Officer of the Valiant at the war’s end. A succession of ‘royal appointments’ ensued in the 20s and 30s, commencing with his command of the Malaya during the Duke of Connaught’s visit to India in early 1921. He was appointed C.V.O. (London Gazette 25 March 1921, refers) and advanced to Rear-Admiral. He then served as Officer Commanding H.M.’s Yachts during the period of King George V’s cruise in the Mediterranean, and was appointed K.C.V.O. (London Gazette 22 April 1925, refers). ...

The M.V.O. group of three awarded to Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Lascelles, The Rifle Brigade, formerly Aide-de-Camp to Sir William Peel as a fifteen year old Naval Cadet with Shannon’s Naval Brigade The Royal Victorian Order, M.V.O. (4th Class) breast badge, silver-gilt, gold and enamels, the reverse officially numbered 434, in its Collingwood & Co case of issue, this also numbered 4/434; Indian Mutiny 1857-59, 1 clasp, Lucknow (H. A. Lascelles, Naval Cadet. Shannon) fitted with silver ribbon buckle, first initial corrected; Ashantee 1873-74, 1 clasp, Coomassie (Capt. H. A. Lascelles, 2nd Bn. Rifle Bde. 1873-4) fitted with silver ribbon buckle, contact marks, otherwise about very fine, the first extremely fine (3) £5,000-£7,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Brian Ritchie Collection, March 2005. Henry Arthur Lascelles, the fourth son of the Right Honourable W. S. S. Lascelles, P.C., M.P., and the eldest daughter of the 6th Earl of Carlisle, was born on 4 December 1842, and entered the Royal Navy in 1855. In March 1857 he was one of seven Naval Cadets who sailed in H.M.S. Shannon (510 officers, men and boys, under Captain William Peel, V.C., R.N.) for the China Station. On the Shannon being diverted to India and the formation of the famous Naval Brigade, Lascelles accompanied the first party of 408 officers and men under Peel’s personal command up the Ganges on 18 August 1857, to Allalahabad, where the entire Brigade concentrated by 20 October. On the 27th, Lascelles continued the journey up country to Cawnpore with a party of 170 men and two 8-inch howitzers under, Shannon’s gunnery officer, Lieutenant Young, R.N. However, when the larger part of this detachment went on with the main body of the Naval Brigade to take part in the Second Relief of Lucknow, Cadets Lascelles and Watson, both barely fifteen years old, were left behind in an entrenched camp north east of Cawnpore with Lieutenant Hay’s rifle company of some fifty Bluejackets and Marines, and two naval 24-pounders, in General Windham’s force. Towards the end of November 1857 a body of rebels, which was being continually reinforced, appeared to the south of the city. To prevent them concentrating, Windham applied to Sir Colin Campbell for permission to take offensive action. Having received no answer after a week he determined to attack the main body. On the 25th a successful advance was made and four guns were taken from the mutineers of the Gwalior Contingent. Three days later, however, Windham was surprised by the enemy who opened a rapid artillery fire on the British forward camp. The Naval guns were immediately sent up to the junction of the Delhi and Calpee roads and returned fire for half an hour before running out of ammunition, whereupon the enemy infantry came on in strength and the British infantry, consisting of two battalions of the Rifle Brigade and H.M’s 88th Regiment, were ordered to fall back. As the Bluejackets and Marines were frantically trying to harness their guns to bullock teams, a shrapnel shell burst overhead causing the draught animals to stampede. In the words of Cadet Watson it then became ‘a case of every man for himself’, and the guns were temporarily abandoned. The ensuing rescue bid to retrieve the guns was made by the Bluejackets, the 88th and the Rifle Brigade who used their rifle slings in place of the missing traces. Lascelles, having determined to distinguish himself, went forward with the rescue party, but being too small and lacking the strength to be of much use in dragging the guns away, seized instead the rifle of a wounded man of the 88th Regiment and joined them in a bayonet charge. With the evacuation of Lucknow completed, Sir Colin Campbell returned to see off the rebel forces harassing Windham’s entrenchment. Cadet Watson wrote, ‘On the 29th Lascelles and I were looking over the parapet when we saw a round shot kick up the dust just outside, and over it came, just over us. Lascelles slipped and I bobbed to avoid it, and over we went both of us together! Such a jolly lark we had, and everyone laughing at us. On the 30th Sir Colin Campbell, from Lucknow, having heard the news of our being shut up, arrived with a large force to our rescue, with jolly old Captain Peel.’ Peel, the remarkable son of the great statesman, Sir Robert, now appointed Lascelles and Watson his Aides-de-Camp. Captain Oliver Jones, R.N., a Half-Pay officer who had come out to India ‘for a lark’ to see what fighting could be done, was evidently impressed with the youngsters’ sang froid: ‘Peel’s A.D.C’s’ he wrote, were ‘fine little Mids., about fifteen years old, who used to stick to him like his shadow under whatever fire he went, and seemed perfectly indifferent to the whizzing of bullets or the plunging of cannon-balls’. Early on the morning of the Third Battle of Cawnpore, on 6 December, Peel called his A.D.C’s and told them that there was to be ‘a grand attack’ and that they were ‘not to run and blow and go head over heels and get out of breath’. At about nine o’clock they moved off on foot, jogging alongside Peel’s horse, and after a preliminary bombardment of the rebel position, the enemy were driven back. The real work of the day then began with Lascelles and Watson joining the pursuit through and beyond the rebel camp for no less than ten miles. ‘It was most awfully exciting’, Watson told his Mama afterwards, though he was also forced to admit, ‘the only way I could keep up ... was to say to my self “Hoicks over, Hoicks over, Fox Ahead!”’. That night Lascelles and Watson slept deeply if not comfortably under a captured gun. Lascelles went on to take part in the capture of Futtehghur, the action of Kallee Nuddee and the final capture of Lucknow where with Mate Edmund Verney, Lieutenant Vaughan and Midshipman Lord Walter Kerr, he went forward amidst the dead and the dying to have a look at the Kaiserbagh. Here, however, they met Sir Colin Campbell who interrupted their sight seeing by ordering them to man a captured gun and turn it on the enemy still holding out close by. For his services in the Mutiny Lascelles received a mention in despatches on 29 July 1858 from Vaughan, who had been instructed by the late and much lamented Sir William Peel, who had died from smallpox, to write a letter to their Lordships at the Admiralty giving an account of the movements of the Brigade and bringing to their Lordships attention those whom he had not had the opportunity of publicly mentioning in despatches. Thus, Vaughan concluded his list with the names of Mr H. A. Lascelles and Mr E. S. Watson, ‘Aides-de-Camp to Sir William Peel, and always in attendance on him in action.’ In 1860, Lascelles left the Navy and was commissioned Ensign in the Rifle Brigade. Promoted Lieutenant in 1865 and Captain in 1872, he embarked with the 2nd Battalion in 1874 to take part in the second phase of the Ashanti War, during which he was present at the battle of Amoaful, advance guard skirmishes and ambuscade actions between Adwabin and the River Ordah, the battle of Ordahsu and the capture of Coomassie. He retired as a Major in February 1882 and was given the Honorary rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. He married the following year, Caroline, the daughter of the Hon. C. Gore, and became Assistant Private Secretary to the Secretary of State for War. He eventually settled in West Sussex at Woolbeding House, near Midhurst, where he was instrumental in raising considerable funds for the building of the King Edward VII Sanatorium a...

The magnificent G.C.B., G.C.V.O. group awarded to Admiral of the Fleet Sir Charles Frederick Hotham, Royal Navy, the only man known to have been eligible for two differently dated New Zealand campaign medals The Most Honourable Order of the Bath, G.C.B. (Military) Knight Grand Cross set of insignia, comprising sash badge, 18 carat gold and enamels, hallmarked London 1887, and breast star, silver with gold and enamel appliqué centre; The Royal Victorian Order, G.C.V.O., Knight Grand Cross set of insignia, comprising sash badge and breast star, silver-gilt and enamels, both pieces unnumbered; Jubilee 1887, clasp, 1897, silver; Coronation 1902, silver; Coronation 1911; New Zealand 1845-66, reverse dated 1860 to 1861 (Chas. Hotham. Midn. & Lieut. Naval Brigade 1860. 61. 63. 64.) officially engraved naming; Egypt and Sudan 1882-89, dated reverse, 1 clasp, Alexandria 11th July (Capt: C. F. Hotham. C.B. R.N. H.M.S. “Alexandra.”); Khedive’s Star, dated 1882, unless otherwise described, very fine or better (10) £8,000-£10,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Douglas Morris Collection, Dix Noonan Webb, February 1997; Alan Hall Collection, June 2000. Charles Hotham was born on 20 March 1843, a descendent of Baron Hotham (created 1621). He entered the Royal Navy as a Naval Cadet aboard H.M.S. Forte on 14 February 1856, and served aboard James Watt and Cordelia from 1857 to 1860, receiving promotion to Midshipman in February 1858. He joined Pelorus from 27 December 1860 to December 1862, and whilst in this vessel he took part in the early actions of the Second Maori War in 1860-61. He was promoted to Sub Lieutenant on 20 March 1862, and to Lieutenant on 17 February 1863 whilst at Excellent. His next appointment was to Curacoa on 20 April 1863, in home waters but this vessel was subsequently transferred to the Australian Station and was quickly engaged in action during the latter part of the Second Maori War. Hotham saw action during a frontal assault on 20 November 1863, on the Maori Redoubt at Ragariri by 90 seamen, armed with revolvers and cutlasses, from H.M. Ships Eclipse, Curacoa and Miranda, under Commander R. C. Mayne, where they were twice repulsed. During another immediate assault led by Commander Phillimore and Lieutenant Downes, First Lieutenant of Miranda, on 20 November 1863, Charles Hotham suffered a severe gun shot wound in the lower half of his right leg. The Surgeon reported ten days later than he was doing well. Hotham's conduct was favourably noticed by Commodore Wiseman on 30 November 1863 and was reported to the Admiralty (London Gazette 13 February 1864). Some time previously he had been sent in charge of a detached party of seamen to escort a Military Officer across mud flats in the rear of the enemy's position, 'for which services he was specially mentioned'. He was also Mentioned in Despatches on a further three occasions (see London Gazettes of 13 February 1864, 19 February 1864, and 15 July 1864). The Admiralty authorised his promotion to Commander as soon as possible commensurate with his completion of the correct amount of sea time by London Gazette 15 July 1864. He received his promotion to Commander on 19 April 1865 when he was only 23 years old, and after being paid off from Curacoa in July 1865, he was placed on half pay for two years. Hotham’s next appointment was the Command of Jaseur from 1867 to 1871, where he received promotion to Captain on 29 December 1871, aged 28 years. He subsequently Commanded Charybdis from 1877 to 1880, and served as Flag Captain of Alexandra from November 1881 to February 1883. In the latter vessel he was engaged during the Egyptian War in the attacks on the forts at Alexandria, and was publicly thanked for his services four days later on 15 July 1882. He was appointed Chief of Staff of the Naval Brigade, and by London Gazette dated 19 July 1882 was awarded the C.B., and Osmanieh 3rd Class. Hotham commanded Ruby from April 1885 to March 1886, and during 1887 he was appointed Assistant to the Admiral Superintendent of the Naval Review and was awarded the Jubilee Medal. He was promoted to Rear-Admiral on 6 January 1888, aged 45 years, and appointed a Lord of the Admiralty from January 1888 to December 1889. His next appointment was Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Station from 1890 to 1893, flying his flag aboard Warspite. He was promoted to Vice-Admiral on 1 September 1893 and awarded the K.C.B. on 24 May 1895. From December 1897 until July 1899 Hotham was Commander-in-Chief Sheerness, flying his flag aboard Wildfire. Following Promotion to Admiral on 13 January 1899, he was appointed Commander-in-Chief Portsmouth in October 1900, until promoted to Admiral of the Fleet on 30 August 1903. At the Funeral of Queen Victoria on 2 February 1901, he was a supporter of the Royal Coffin, and was subsequently awarded the G.C.V.O. He was awarded the G.C.B. on 9 November 1902 for services at the Coronation of King Edward VII. Hotham died on 22 March 1925. He is the only man known to have been eligible for two differently dated New Zealand Campaign Medals, serving aboard Pelorus as a Midshipman for the 1860-61 Campaign, and aboard Curacoa as a Lieutenant R.N. for the 1863-64 battles. Men who fought in two separately dated actions were not entitled to a clasp (or a second differently dated Medal) for their additional participation. When such an instance occurred, as happened in this unique case, it was marked solely by extra details engraved on the edge of his 1860-61 dated Medal (i.e., 'Midn and Lieut Naval Brigade 1860-61-63-64'). He also received the rare distinction of being awarded all of the Jubilee and Coronation Medals issued between 1887 and 1911. Charles Hotham’s obituary given in The Times, 22 March 1925, states: ‘Admiral of the Fleet Sir Charles Hotham, G.C.B., G.C.V.O., the Senior Officer of his rank in the Royal Navy, whose death was announced, came of a distinguished naval family which has given many sons to the Imperial Forces. The eldest son of Captain John Hotham, his great Grandfather was a brother of the first Baron Hotham and thus the Admiral of the Fleet was related in the second and third degree to innumerable other naval officers. He gravitated to the Royal Navy almost as a matter of course, and won early advancement to the highest positions. He was a member of that important Board of the Admiralty which, under Lord George Hamilton, was responsible in 1889 for the great Naval Defence Act, which considerably raised the strength of the Fleet and placed the sea power of the Empire on a firm basis. Although he later held high Command afloat, and filled administrative posts ashore, it was not his good fortune to participate in the war work of the Fleet which he had helped to create. He had, however, the rare distinction of being appointed Commander in Chief on three occasions, China, the Nore and Portsmouth. ‘Charles Frederick Hotham was born on 20 March 1843 and entered the Royal Navy in 1856 when he was barely 13. He was not yet 20 when he was promoted to Lieutenant and, while serving in this rank in Curacoa, flag ship on the Australian Station, he was engaged in the New Zealand War of 1863 where, in Command of a party of small arm men, he repeatedly distinguished himself, and especially at the attack on Rangariri in November 1863. His conduct was favourably reported at the Admiralty and backed up by his previous good record. He obtained Commander's rank as soon as he had completed the required two years Lieutenant's service. From 1867 to 1870 he Commanded the Jaseur, screw gun vessel serving in the Mediterranean and on the West Cost of Africa and in December 1871 being ...

The 3-clasp Naval General Service medal awarded to Lieutenant John Meares, Royal Marines, for his services as 2nd Lieutenant on board the Active, being wounded in action at Lissa and mentioned in despatches Naval General Service 1793-1840, 3 clasps, 28 June Boat Service 1810, Lissa, Pelagosa 29 Novr. 1811 (John Meares, 2nd Lieut. R.M.) original ribbon, toned, extremely fine £12,000-£16,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Peter Dale Collection, July 2000. 25 clasps issued for Boat Service 28 June 1810, 123 clasps issued for Lissa; and 64 clasps issued for Pelagosa 29 Novr. 1811. Capture of twenty-five vessels at Grao, 28 June 1810 ‘The British frigates, Active, thirty-eight, Captain J. Gordon, and Cerberus, thirty-two, Captain H. Whitby, under the orders of Captain W. Hoste, of the Amphion, thirty-two, were cruising in the Gulf of Trieste, in the month of June. On the morning of June 28th, the Amphion chased a convoy laden with naval stores for the arsenal at Venice, into the harbour of Grao. Captain Hoste decided upon the capture or destruction of the vessels, which, owing to the shoals, could be effected only by boats. In the evening he signalled to the Active and Cerberus, to send their boats to him at midnight, but owing to her distance in the offing the Active was unable to obey the signal in time. At the hour appointed the boats of the Amphion and Cerberus, commanded by Lieutenant W. Slaughter, second of the Amphion, assisted by Lieutenants D. O'Brien, and J. Dickenson, pushed off, and before daylight landed a little to the right of the town. On advancing the British were attacked by a body of French troops, and armed peasantry, who were charged with the bayonet, and a sergeant and thirty-five men made prisoners. The town was then entered, and the vessels, twenty-five in number, taken possession of, but it being low water, it was late in the evening, and only after great exertions they were got afloat, and over the bar. In the mean time the boats of the Active came up, and assisted in repelling another attack of the enemy, taking their Commander and twenty-two men prisoners. Five vessels were brought out with their cargoes, and a number of small trading craft, laden with the cargoes of eleven vessels which were burnt. At eight p.m., the boats and the prizes had joined the ships, which had anchored about four miles from the town. The loss of the victors in this dashing affair, was four men killed, and Lieutenant Brattle of the Marines, and seven men wounded. Lieutenant Slaughter was promoted to the rank of Commander in the month of November following.’ (Medals of the British Navy by W. H. Long refers). Action off Lissa, 13 March 1811 ‘In 1811, Captain W. Hoste in the Amphion, thirty-two, having under his command the Active, thirty-eight, Capt. J. A. Gordon; Cerberus, thirty-two, Captain H. Whitby; and the Volage, twenty-two, Captain P. Hornby, was cruising in the Adriatic. On March 13, off the Island of Lissa, he met with a French squadron of four French and Venetian frigates of forty guns each, two of thirty-two guns, a corvette of sixteen guns, and four smaller vessels, more than double his force. Hoste formed his line of battle, and with the signal, ‘Remember Nelson’ at his masthead, awaited the attack of the enemy, who bore down in two divisions and attempted to break his line. They were received by so well directed a fire that their leading ship La Favourite became unmanageable, and in endeavouring to wear, ran on the rocks. Part of the French squadron then engaged the British to leeward, while their other ships continued the action to wind-ward, thus placing Hoste between two fires, a French frigate taking her station on the lee quarter, and a Venetian frigate on the weather quarter of the Amphion. After a severe contest both were compelled to strike.. The remainder of the enemy then bore off, the Amphion was too crippled to pursue, but the Active and Cerberus chased and captured the Venetian frigate Corona of forty-four guns. Another French frigate, which had struck her colours and surrendered, taking advantage of the disabled state of the Amphion stole off, and with the smaller vessels escaped. The French Commodore Dubourdieu was slain in the action, and his ship being on the rocks was set on fire by her crew and destroyed. The loss of the British was fifty men killed and one hundred and fifty wounded. The loss of the French was much greater. (Medals of the British Navy by W. H. Long refers). The Alceste, Active and Unitié with French frigates, 29 November 1811 On November 29th, as the thirty-eight gun frigates Alceste, and Active, Captains M. Maxwell, and J. A. Gordon, and Unitie, thirty-two, Captain E. Chamberlayne, were cruising in the Adriatic, near the island of Augusta, three strange sail appeared, which proved to be the French forty-gun frigates Pauline, and Pomone, and the frigate built store ship Persanne, from Corfu to Trieste, laden with brass and iron ordnance. On discovering the British frigates, the French ships made sail to the north west, and were chased by the Alceste, and her companions. At eleven a.m. the Persanne finding she could not keep way with the Paulino and Pomone separated from them, and bore up before the wind, and the Unitie was ordered by Captain Maxwell to go in pursuit of her. The Alceste and Active continued the chase of the Pauline and Pomone, and at twenty-four minutes past one p.m. the Alceste under a press of sail to get alongside the French Commodore, a short distance ahead, exchanged broadsides with the Pomone, but a shot carrying away her main top-mast, the wreck fell over on the starboard side, and the Alceste dropped astern. Cheers of ‘Vive l'Empereur,’ arose from both the French ships, but the Active coming up, took the place of the Alceste, and brought the Pomone to close action about two p.m. Shortly after, the Pauline stood for the Alceste and both ships about half-past two p.m. became closely engaged. After an action of thirty minutes, the French Commodore, seeing that the Pomone was getting the worst of it with the Active, and observing the eighteen-gun sloop Kingfisher, Captain E. Tritton, approaching in the distance, hauled his wind, and stood to the westward under all sail. The Alceste then ranged up on the larboard beam of the Pomone and opened fire on her, the Active having unavoidably shot ahead. The main and mizzen masts of the Pomone fell overboard, and immediately afterwards she hoisted a Union Jack in token of surrender. Neither of the British frigates being in a condition to pursue the Pauline, the French Commodore escaped, and reached Ancona in safety. In the mean time the Unitié pursued the Persanne and was galled considerably by her stern chasers. About four p.m. the British frigate got near enough to open her broadside, the Persanne returned it, and immediately hauled down her colours. The sails and rigging of the Unitié were considerably damaged, but she had but one man wounded. The Persanne had two men killed, and four men wounded. The casualities on board the Alceste, out of a crew of two hundred and eighteen men and boys, were a midshipman and six men killed, and a lieutenant and twelve men wounded. The Active had a midshipman and seven men killed, her gallant captain lost a leg, and two lieutenants and twenty-four men were wounded. The fore-mast of the Pomone fell soon after her capture, and her hull was so shattered by the well directed fire of the Active that she had five feet of water in her hold. Out of her crew of three hundred and thirty two men, fifty were killed and wounded, among the latter being her cap...

The extremely rare inter-war Palestine D.S.M. pair awarded to Stoker Petty Officer H. J. Shorter, Royal Navy, a volunteer from H.M.S. Barham who was wounded whilst serving as a train guard during the volatile General Strike of 1936 Distinguished Service Medal, G.V.R. (K.28338 H. J. Shorter, S.P.O., R.N. Palestine 1936) impressed naming, official correction to first four letters of ‘Palestine’; Naval General Service 1915-62, 1 clasp, Palestine 1936-39 (K.28338 H. J. Shorter, S.P.O. R.N.) some edge bruising to the first, otherwise very fine and better (2) £3,000-£4,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- Provenance: Douglas-Morris Collection, Dix Noonan Webb, February 1997 - DSM only, since reunited with NGS. Just three D.S.M.s were awarded for the pre-war operations in Palestine, all in 1936, out of an equally rare total of 10 D.S.M.s for the entire inter-war period. D.S.M. London Gazette 6 November 1936: ‘For gallant and distinguished services rendered in connection with the emergency operations in Palestine during the period 15 April to 14 September 1936.’ Henry Jack Shorter was born in Shaftesbury, Dorset, on 21 April 1896, and joined the Royal Navy as a Stoker 2nd Class in October 1915. Having then served ashore in Victory II, he joined the cruiser H.M.S. Doris in the following year and remained similarly employed until the war’s end. Advanced to Stoker Petty Officer in October 1930, and awarded the L.S. & G.C. medal February 1931, he joined the battleship Barham on the Mediterranean station in August 1935. When a general strike was declared in Palestine on 20 April 1936, it was feared the country’s railway system would be crippled. High on the list of the local authorities’ concerns was the onward transportation of cargo landed at the ports of Jaffa and Haifa. In consequence, a call went out for volunteers from ships of the Fleet lying at Alexandria, including H.M.S. Barham, and 13 railway crews of an engine driver and fireman were formed, in addition to further ratings being trained in a variety of other related disciplines, including signalling. By the summer, extremists were responding with acts of sabotage and intimidation, and the volunteer train crews - who managed to maintain a sixty percent service - received a two-man armed guard. Nonetheless, the actions of the extremists were highly effective, incorporating as they did the removal of railway track, and the use of explosive devices on the rails. Another, and most unpleasant form of sabotage, because of the difficulty in seeing it, was the widening of the gauge so that trains came off the rails. On the afternoon of 4 September 1936, a heavy goods train pulled by two engines was derailed by sabotage on the Jaffa to Jerusalem line near Qalqiliya, just north of Lydda, causing the death of a British soldier, a native driver, and five other casualties. In the first engine the native driver was killed and the fireman scalded so badly that he later died. Of the two-man military guard, one was killed and the other injured. In the second engine, the driver and the two-man naval guard were also injured, including Shorter, who was scalded. Here, then, the origins of the award of his D.S.M. By September 1936, large troop reinforcements had arrived, and the military were able to take over all the tasks of the Royal Navy, apart from maintenance of the coastal patrol to guard against gun-running. Sir Samuel Hoare, First Lord of the Admiralty, paid tribute to the naval personnel serving ashore in a speech on 4 September 1936, after a visit to Haifa: “Once again, the Navy has readily met an unexpected emergency. If I wanted an example of its adaptability, what better could I have than an armoured train fitted out and manned by naval personnel?” Shorter was invested with his D.S.M. in June 1937, shortly before he was pensioned ashore. Recalled in the summer of 1939, he joined the destroyer Keppel and shared in her part in evacuating troops from France in May-June 1940, before to removing to the cruiser Penelope in June 1941. Towards the end of the year, Penelope joined Force K in the Mediterranean, and she went on to witness extensive action on the Malta run and elsewhere, so much so that she was nicknamed ‘H.M.S. Pepperot’ on account of damage sustained. Interestingly, Shorter’s service record states that he was surveyed at 64th General Hospital, M.E.F. in early November 1943. He was finally released ‘Class A’ in October 1945. Sold with copied research including contemporary newspaper and Illustraed London News reports with photographic illustrations.

The rare Second War crossing of the Elbe M.M. awarded to Marine D. Towler, 45 Commando, Royal Marines. As a sniper at the crossing of the Rhine in March 1945, ‘he kept the Huns jittery near the factory area in Wesel’, where he ‘killed at least ten and wounded others in thirty-six hours fighting’; as his Troop’s Bren gunner at the Elbe crossing in April 1945, he faced off two enemy attacks: ‘two dead Germans were within 10 yards of his gun and eleven others dead or wounded in the immediate vicinity’ Military Medal, G.VI.R. (EX.4188 Mne. D. Towler. R. Marines.) in its named card box of issue, extremely fine £1,800-£2,200 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- M.M. London Gazette 7 August 1945: ‘For distinguished service whilst attached to the Allied Armies in the invasion operations in North-West Europe.’ The original recommendation states: ‘On the night of the Elbe crossing Mne. Towler was a Bren Gunner in D Troop 45 RM Commando. His Troop became involved in confused street fighting in the dark on its way to its objective. Mne. Towler was ordered to take up a position to cover a flank whilst his Troop pushed on. He selected a position in a house and engaged the enemy immediately. A section attack was put in against his house by the enemy. This was beaten off by steady and accurate shooting. As his ammunition was getting low, Mne. Towler sent his No. 2 of the gun to get more. During his absence another attempt was made by the enemy to dislodge Mne. Towler. Again this was beaten off. When his No. 2 returned together with a sub section to assist, there was only one magazine left containing a few rounds. Two dead Germans were within ten yards of the gun and eleven other dead or wounded in the immediate vicinity. Although Mne. Towler was not actually wounded he was considerably grazed by brick splinters and stones raised by the 2cm. flak guns which were used against his position. Mne. Towler's tenacity and determination was largely responsible for this troop being able to push on, without undue interference, to their objective.’ Douglas Towler was an employee of the Northern Co-operative Dairies in Aberdeen prior to joining the Royal Marines. Having then volunteered for special service, he joined 45 R.M. Commando on its formation in August 1943. As part of the 1st Special Service Brigade under Brigadier Lord Lovat, ‘45’ took heavy casualties on coming ashore on Gold Beach on D-Day, suffering a loss of three officers and 17 men killed or wounded, and one officer and 28 men missing. Those grim statistics were depressingly enlarged upon in the coming weeks of the Normandy campaign, up until ‘45’s’ withdrawal to the U.K. for a ‘refit’ in September 1944 Now part of First Commando Brigade, ‘45’ returned to an operational footing in Holland in January 1945, and was quickly in action at the battle of Montforterbeek, where Lance-Corporal Eric Harden of the R.A.M.C., attached to the Commando, gained a posthumous V.C. A costly attack on Belle Isle on the Mass having followed, among other actions, Towler and his comrades were next deployed to the crossing of the Rhine on the night of 23-24 March 1945. Their objective was Wesel, where Towler received a shrapnel wound but remained on duty. In fact, as evidenced by an accompanying local newspaper report, he took a heavy toll on the enemy: ‘Marine Dougles Towler of 12 Hayton Road, Aberdeen, a former employee of the Northern Co-operative Dairies, was the Commando man who kept the Huns jittery near a factory area in Wesel after the Rhine crossing. With the Jerries sometimes only twenty-five yards away, Towler, a sniper, kept picking them off and killed at least ten and wounded others in thirty-six hours’ fighting. “As the Huns were so near,” he said, “I kept changing my position in case they started mortaring me. Every time one showed himself, I let go at him. I was in the factory area on one side of the railway and the Germans on the other side of the railway lines. On one occasion I noticed they were forming up for a counter-attack, so I covered a little gap in the hedge. Sure enough, the Jerries kept passing by, and I just shot them down. The counter-attack never materialised. A German twelve-man patrol once approached my position, so I opened fire, and the patrol disappeared. As the enemy were so near the only answer was sniping to make them keep their heads down and keep them jittery. I saw many of them when I fired just cut their equipment off and make a bolt for it.” Towler is regarded among his Commando officers as a man who always keeps his finger on the trigger.’ Indeed, Towler certainly lived up to his reputation in Operation ‘Enterprise’, the Elbe crossing on the night of 28-29 April 1945, when ‘45’ were embarked in Buffaloes before advancing on the town of Lauenberg. Here, as cited above, he performed most gallant work in facing off two spirited German attacks with his Bren gun, thereby adding to his growing tally of enemy dead. In his book Commando Men, Bryan Samain relates the story of how Towler’s ‘B’ Troop carried out an attack on an enemy ack-ack battery the following day. In it he refers to ‘a young Scots Bren-gunner, Marine Norman Towler’. Given the latter’s fearless conduct on that occasion, it seems more likely it was in fact Douglas Towler: ‘Moving off under the command of John Day, the Troop closed to within one hundred yards of the battery. At this stage the Germans suddenly opened up, spraying the road and surrounding buildings with a vicious fusillade of 37-millimetre shells. Baker Troop immediately scattered for cover, and the whole street became alive with orange-coloured flashes as the shells smacked and roared into the already shattered fabric of blasted buildings. The men of Baker Troop crouched low behind what cover they could find, awaiting the order to move forward and assault the battery. Meanwhile, as John Day started to shout preliminary orders above the roar of gunfire, a young Scots Bren-gunner, Marine Norman Towler, got to his feet and coolly returned the enemy fire from an exposed position. For some unknown reason the Germans suddenly stopped firing. Perhaps they were too flabbergasted by Towler’s action to continue: but whatever the reason, it made them lose the day, for Baker Troop seized the initiative and rushed the battery. Within minutes the guns had all been overrun, and something like fifty prisoners rounded up, including some German W.A.A.F.s, who emerged coyly from a series of dugouts.’ Towler was discharged from the Commandos in November 1945, when he was described as ‘an exceptionally fine, upstanding type of soldier.’ Sold with a quantity of original documents, including the recipient’s Buckingham Palace forwarding letter for his M.M., his C.O.’s testimonial and character reference, and a letter to his wife regarding his shrapnel wounds in March 1945, together with some wartime newspaper cuttings and a copy of Bryan Samain’s book Commando Men.