We found 4709 price guide item(s) matching your search

There are 4709 lots that match your search criteria. Subscribe now to get instant access to the full price guide service.

Click here to subscribe- List

- Grid

-

4709 item(s)/page

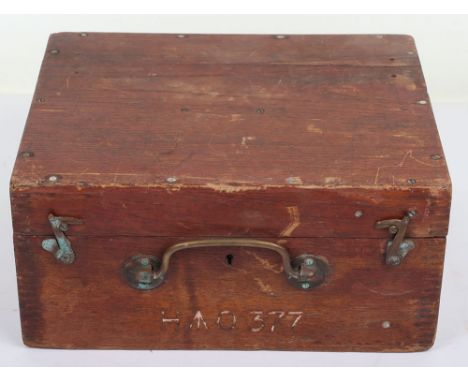

Collection of Aviation Navigational equipment. Air Ministry Bubble Sextant. Number 14358/42. Serial number 11836/42. In original wooden case. Navigators chart board lamp. MkI Table sliding rule 6B232. 2X Mk II cockpit lamps, Ref' number 5C/366, red filter in one. Morse code tapper dated 1940. Range and Endurance computer MkI in webbing sleavePOA https://www.bradleys.ltd/quotation-request-form

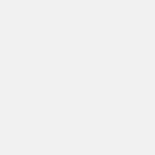

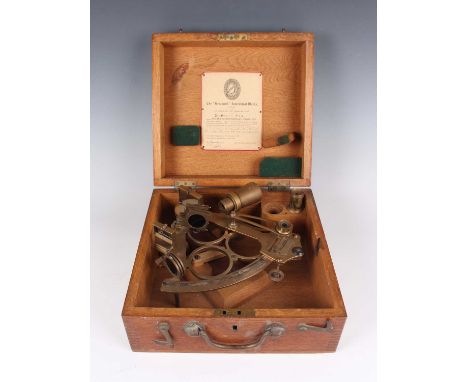

THREE ANTIQUE NAVIGATION TOOLS comprising an Elliott Brothers of London pocket sextant in integral case, a boxed Negretti & Zambra brass protractor and a Cail of Newcastle brass compass with etched face (Est. plus 24% premium inc. VAT)Condition Report: A small item missing from the Negretti box, some oxidation to the compass, sextant appears generally good.

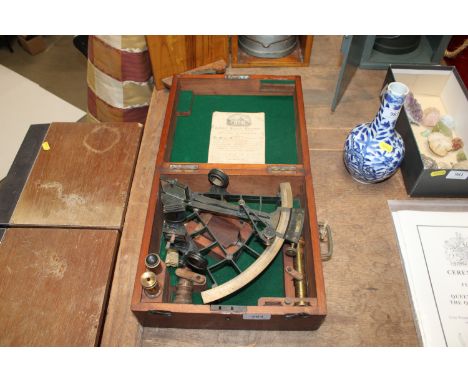

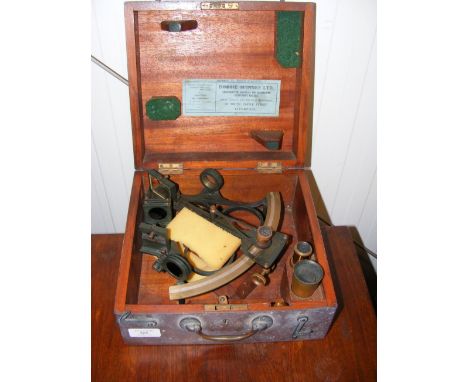

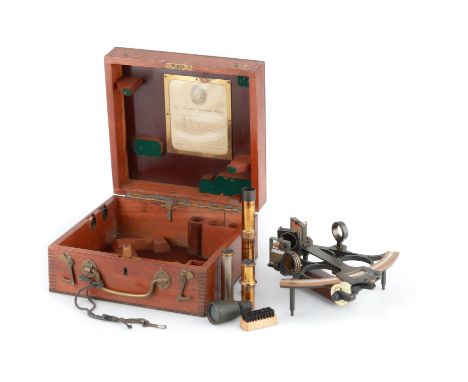

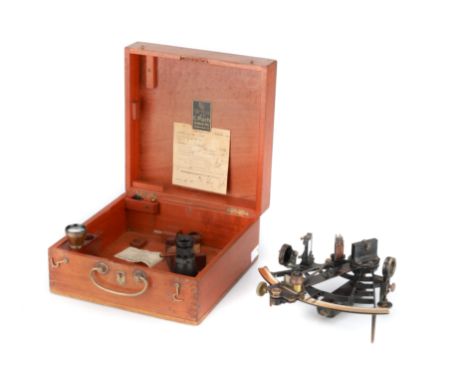

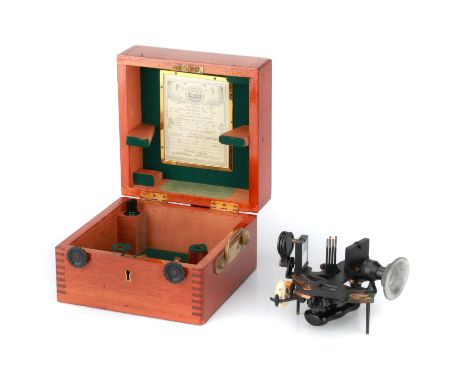

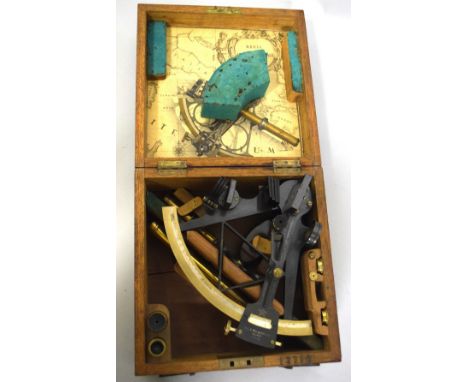

WWII, Husun Herny Hughes, Flying Boat 3 1/2 inch Sextant,English, dated 1941, engraved REF No.68/177 and numbered 44368 with trade label to lid for Husun, Henry Hughes & Son Ltd, finished in black crackle paint in polished fitted caseFootnote: Henry Hughes Nautical Sextant, model 6B/177, is a fascinating artefact that bridges the worlds of maritime and aviation history. Built by London-based firm Henry Hughes & Son, this sextant is a remarkable example of technological ingenuity from the Second World War.This particular model was specifically designed for use aboard the Sunderland flying boats, these aircraft that played a vital role in the Allies' fight against German U-boats. The Sunderland was a four-engine flying boat renowned for its endurance and versatility, patrolling vast stretches of ocean. For such missions, precise navigation was absolutely critical, and the Hughes 6B/177 sextant was a key tool to ensure that.Interestingly, this instrument holds the distinction of being the only marine sextant adapted for use in the air. It was specially built to maintain the high level of accuracy required for the Sunderland's long reconnaissance flights.However, there’s a twist to its story. Despite its innovative design, it seems the sextant was rarely, if ever, used during actual flights. Marine sextants, while excellent on calm waters, struggled to perform effectively in the dynamic and often turbulent conditions of the air. Instead, flight crews relied on the bubble sextant, which was far better suited to the challenges of aerial navigation.That said, the Henry Hughes sextant wasn’t without its purpose. When the Sunderland flying boats landed on the water, the sextant came into its own. Stationary on the ocean’s surface, it was used for traditional navigation.

‘If their escape was remarkable, that of the men in No. 4 boat was even more so. This was the boat to which Able Seaman S. H. Light went when ordered to abandon ship. Sydney Light was the rarest of rare men, an Admiral Crichton in real life whose versatility was astonishing. As an Able Seaman he was unique in as much as he carried a sextant in his kit. When he went to sea he liked to know where he was and his sextant, with the aid of the sun and the stars, told him. Whether he was born with the Midas touch or whether he acquired it is anybody’s guess, but his business instinct and flair for making money led to his truly remarkable rise from deck boy to Underwriting Member of Lloyd’s.’ So states a chapter entitled The Amazing Able Seaman. The outstanding Second War George Medal and Lloyd’s Medal for Bravery at Sea group of six awarded to Sub-Lieutenant S. H. Light, Royal Naval Reserve, late Merchant Navy, otherwise known as the ‘Amazing Able Seaman’ - for that was his rate at the time of his G.M.-winning exploits in an epic open boat ordeal after his ship was torpedoed in the Atlantic in November 1940; he ran away to sea aged 13, travelled the globe, and then returned home to establish a string of successful businesses; by the outbreak of war, he had gained a private pilot’s licence, raced in Monte Carlo rallies and was safely on his way to becoming a Lloyd’s name, none of which, however, prevented his volunteering for the Merchant Navy George Medal, G.VI.R. (Sydney Herbert Light); 1939-45 Star; Atlantic Star; Defence and War Medals 1939-45; Lloyd’s War Medal for Bravery at Sea, silver-gilt (Able Seaman S. H. Light, M.V. “Port Gisborne” 11th October 1940) with original gilt embossed leather case of issue and named card box of issue for campaign medals, the first five mounted as worn, extremely fine (6) £5,000-£7,000 --- Importation Duty This lot is subject to importation duty of 5% on the hammer price unless exported outside the UK --- --- G.M. London Gazette 4 February 1941, in a joint citation with Captain Thomas Kippins, Master of the M.V. Port Gisborne, who was awarded the O.B.E.: ‘The ship was torpedoed at night and it was decided to abandon her. Captain Kippins took charge of No. 2 boat with 26 men on board, and during the night two others were rescued from the water with great difficulty. The boat was nearly overturned by heavy seas. Four men washed overboard were rescued, but the mast, sails, and several oars were lost, and the boat filled to the thwarts. She was righted and two more of the crew were picked up. The sea-anchor having been lost, the men had to use the oars all through the night. The sea calmed down the next day and they made a sail and hoisted it, using the boat-hook as a mast. For the next 14 days, often in heavy seas, tired out and short of water, they rowed and sailed. Suffering from weakness, cold and hardship, they were found at last by a merchantman and brought into port. Captain Kippins never faltered during the whole voyage and his stout heart and good seamanship saved the lives of his men after facing what seemed almost certain death. Another boat from the ship was swamped while being lowered and all the hands except Able Seaman Light and a greaser were thrown into the sea. While Light released the forward fall and the greaser held the boat off, eight men got aboard. The seas swept over the boat as she lay broadside on and the following morning she was still awash with her crew worn out through baling. Seaman Light, who had taken command, stepped the mast and set sail. Heavy rain added to their hardships, but Light kept them in good heart. They sailed on until they came across a boat containing 16 men from another torpedoed ship. Light took her in tow, though the sea and the wind were rising, so that they had to bale all the time. They sighted a rocky shore and decided to lay off until dawn, but the boats were drifting out to sea again. In a dead calm the men rowed all day till they were worn out. Those in the other boat were despairing, and Seaman Light entered it and massaged two men, gave them his stockings, and dressed their wounds. In his own boat he massaged a deck boy who was in great pain and bound up his feet. After ten days of privation, weariness and danger the exhausted crews were rescued by a British ship. By his courage, leadership and self-sacrifice Seaman Light was the means of saving the crews of the two boats.’ Lloyd’s Medal for Bravery at Sea Lloyd’s List & Shipping Gazette, 3rd List of Awards, 30 July 1941. Sydney Herbert Light was born in Limehouse in the East End of London on 12 June 1904, the son of a publican. Threatened with expulsion from Margate College, aged 13, and being ‘independent by nature and a born leader’, he rebelled at the suggestion and chose instead to run away to sea, the commencement of his remarkable progression from deck boy to Lloyd’s name. By the time he came ashore two or three years later, he had amassed savings of £100, with which he set up a coal transport business. The rest, as they say, is history, and that remarkable history is related at length in the above cited source – The Amazing Able Seaman. But the following summary of Light’s pre-war life – as provided by an engineer officer of the Port Gisborne – is an excellent summary: ‘S. H. Light, A.B., ex this vessel, went to sea at the age of 13 years and remained at sea until he was 20 years of age. He was at one time an O.S. on the S.S. Port Hacking. After leaving the latter vessel he started coal carting in Great Yarmouth with one cart. This was the basis of his start in life, and after a while he had 6 carts. He then sold his business and started a road transport organization which also did well. To-day Mr. Light is the licensee of the Southborough Hotel, Kingston Bye-Pass, Surbiton. He has no sea-faring certificate, but owns his own 25-ton yawl, and has sailed down the Mediterranean as far as Monte Carlo. At Monte Carlo he has taken part in motor car racing and has been presented with a magnificent gold cigarette case from the S.S. Company [Swallow Sidecar Co., later Jaguar Cars]. He signed on the M.V. Port Gisborne to ‘do his bit’ during the war. From his full report, it is evident he knew his job very well. He always carries his own sextant, which has been lost, and the Company is presenting him with a new one which will be mounted with a plate to commemorate his service in navigating the ship’s boat for 10 days. Light has owned his own hunters and has hunted a good deal. He is also a first-class skier and has been in the habit of going to Switzerland every year. He also enjoys a handicap of 2 at golf. Besides all these accomplishments he has an air navigator’s certificate and a “B” licence. He is now waiting to sit for his Yacht Master’s ticket. Dated 4.11.1940.’ Of events when the M.V. Port Gisborne was torpedoed and sunk by the U-48 in the Atlantic on 11 October 1940, about 350 miles west of Ireland, when sailing in Convoy HX77 from Bermuda to England, the extraordinary fortitude and leadership of Light stood out. In summarising his role in command of boat No. 4, the Awards Committee concluded: ‘During the whole of the 10 days’ voyage in the Port Gisborne’s boat, Able Seaman Light proved himself well worthy of leadership, navigating the boat, organising routine, giving first aid where required and displaying fine seamanship. He was, moreover, able to keep a log of the whole voyage. By his seamanship, fortitude and adaptability, Able Seaman Light was undoubtedly responsible for the safe deliverance of his own and the St. Malo’s survivors, a ...

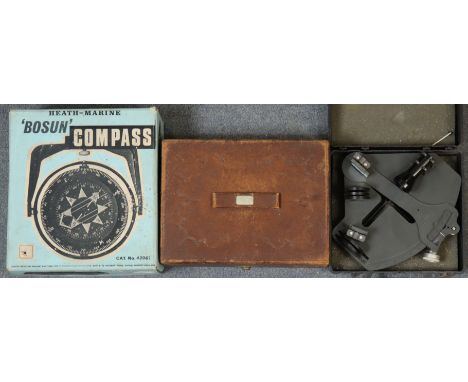

Victorian brass four drawer telescope with a pale mahogany barrel and brass lens cap, inscribed Worthington & Allen, London, L.55cm extended; small Troughton & Simms military sextant, cased; military compass, the leather case stamped L. F. & Co., 1916; pair of Ross Steplux 7 x 50 binoculars, pair of leather bound binoculars, Princess Mary Christmas tin, A.R.P. whistle, Welsh Miner's Lamp, E. Thomas & Williams, Aberdare, and other items. (a lot)

Air Ministry, WWII, Husun Herny Hughes, Flying Boat 3 1/2 inch Sextant, English, dated 1943, engraved A.M. REF No.68/177 and numbered 35147 with trade label to lid for Husun, Henry Hughes & Son Ltd, finished in black crackle paint in polised fitted case Footnote: Henry Hughes Nautical Sextant, model 6B/177, is a fascinating artefact that bridges the worlds of maritime and aviation history. Built by London-based firm Henry Hughes & Son, this sextant is a remarkable example of technological ingenuity from the Second World War. This particular model was specifically designed for use aboard the Sunderland flying boats, these aircraft that played a vital role in the Allies' fight against German U-boats. The Sunderland was a four-engine flying boat renowned for its endurance and versatility, patrolling vast stretches of ocean. For such missions, precise navigation was absolutely critical, and the Hughes 6B/177 sextant was a key tool to ensure that. Interestingly, this instrument holds the distinction of being the only marine sextant adapted for use in the air. It was specially built to maintain the high level of accuracy required for the Sunderland's long reconnaissance flights. However, there’s a twist to its story. Despite its innovative design, it seems the sextant was rarely, if ever, used during actual flights. Marine sextants, while excellent on calm waters, struggled to perform effectively in the dynamic and often turbulent conditions of the air. Instead, flight crews relied on the bubble sextant, which was far better suited to the challenges of aerial navigation. That said, the Henry Hughes sextant wasn’t without its purpose. When the Sunderland flying boats landed on the water, the sextant came into its own. Stationary on the ocean’s surface, it was used for traditional navigation.

-

4709 item(s)/page